Make Your Own Buttons with a Gel Touch Screen

Touch screens are versatile and easy to use, but the slick surface isn’t great for some tasks—typing more than a quick e-mail, for instance—and becomes pretty useless when your eyes are occupied with other tasks.

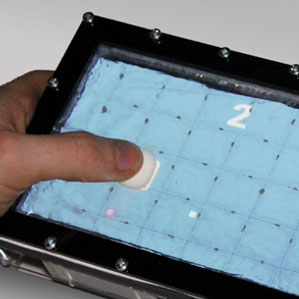

With all this in mind, researchers hailing mainly from the Technische Universität Berlin in Germany built a prototype of a touch screen with a layer of gel atop it that can change from soft to stiff when heat is applied—making it possible to create temporary buttons in all kinds of shapes that needn’t be defined in advance, which users can feel and use to interact with the display.

Such technology could make it easier to use a range of electronics, from in-car displays to smartphones and wearable gadgets, to do things like receive alerts or input information without needing to glance at the devices themselves. A paper on the work will be presented in November at a user-interface conference in North Carolina.

With the prototype, a seven-inch touch screen called GelTouch, researchers stiffened the gel into three basic shapes to form a grid of buttons, a slider, and a one-finger joystick button. They tried these out with several different sample applications: using the buttons to dial a phone number without looking at the display, the slider to scroll through an array of photos, and the joystick to play a simple game.

“You basically can have unlimited shapes or structures or whatever you want,” says Viktor Miruchna, the lead author of the paper who created GelTouch as a graduate student at TU Berlin.

To make GelTouch work, researchers used a heat-responsive hydrogel atop the display that is transparent and jelly-like until it’s heated above 90 °F.

Adding heat causes water to evaporate from the gel, collapsing and making it up to 25 times stiffer (while also turning it white). Researchers placed a layer of indium tin oxide (ITO), a transparent conductive film often used in displays, below the gel coating and connected electrodes to it. Then they used a few different methods to heat up the gel, including passing a current from one electrode to the next in order to harden the gel lying between them.

A video shows this in action: when heat is applied to certain parts of the gel, it blooms into a white spot or shape; the longer heat is applied, the bigger the hardened area becomes. When the heat is removed, it soon disappears. To make high-resolution shapes, the researchers also engraved squares in the ITO; they say they could stack several engraved layers of ITO to create a range of shapes.

In the existing prototype, it takes about two seconds to harden once heat is applied and about the same amount of time to soften again. That’s pretty slow, says Hong Tan, a professor at Purdue University who studies haptic technologies, and she notes that cooling down the gel may be especially tricky, among other problems. Still, she says, it’s pretty cool and could be useful for touch screens and flexible displays.

Micah Yairi knows well the challenges with making disappearing and reappearing buttons: he’s cofounder and chief technology officer of Tactus Technology, which sells an iPad case that uses tiny channels filled with fluid to make preconfigured buttons rise from an otherwise flat, clear surface (see “Shape-Shifting Touch Screen Buttons Head to Market”). Yairi says the GelTouch technology sounds clever, though he, too, points out that there are a lot of issues to be solved before it could be truly useful.

For one, if you wanted to have a button that maintained its shape over time, you’d have to figure out how to apply and adjust current in such a way that the button didn’t keep growing due to the surrounding gel heating up, too. There’s also the softness of the display, which is very different from the relatively stiff touch screens we’ve become accustomed to swiping and tapping.

Miruchna, currently an intern doing tech consulting in San Francisco, agrees there is more work to do in order to commercialize the gel pad, and says the researchers already have ideas for solving its issues.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.