Alumni Letters

The Housemaster at NASA

“Did you know your housemaster is working at NASA?” my mom blurted over the phone before I could even say hello. Obviously out of touch with the news, I responded, “Who, Dava? No way. I just saw her at dinner.”

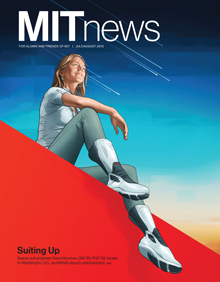

I met Dava Newman (“Suiting Up,” July/August 2015) during my first night in Baker House, when she and her husband, Gui, introduced themselves to the new freshmen. That was the only time I ever heard Dava speak of her work as a Course 16 professor, because after that, our conversations focused on simpler topics than the complexities of flexible membranes in space. I saw Dava everywhere—on campus, in the dining hall, in the gym—and we would talk about everything from our favorite salad dressings to what I was doing over the weekend.

Dava was never catalogued as one of the scary, intimidating MIT professors in my mind. She was a friend, an advisor, and a kind of motherly figure around Baker who always made me smile and feel I was welcome. When I was at my worst, with the stresses of MIT bearing down, seeing Dava and Gui stroll into the Baker dining hall in their gym clothes always made me feel that professors truly are just like us.

I’m sure I can speak for all the Bakerites in saying that we will miss Dava’s presence and the hard work she has put into making Baker what it is today. While she may not be around next year to slip me a few extra taco tickets at the semesterly Taco Truck study break, I know she’ll be helping an even greater cause in Washington, D.C.

Kelly McGee ’17

Cambridge, Massachusetts

System Dynamics in Dresden

Jay W. Forrester shaped my life in unexpected ways back in 2007, when I had the opportunity to chat with him over coffee during an MIT workshop (“The Many Careers of Jay Forrester,” July/August 2015).

When I met Professor Forrester, I was working in Saxony for a premium car manufacturer. Helping ramp up production of the car plant had been like going through a second German reunification at a fast pace as cultures from West and East Germany met to achieve a shared vision. An organization is (in some broader sense) a replication of the larger society, with all its challenges. Policies at the plant and changes in the network of personal relationships there had (often subtle) implications for the overall work outcome, but understanding these dynamics was proving difficult.

At the MIT workshop we discussed learning to see the connections within the larger social field and how they are embedded in existing feedback systems. What still sticks in my mind from my short chat with Jay is his saying, “Don’t fear objection by others—in the end, you learn for yourself!”

With a personal dream to establish a System Dynamics Institute here in Dresden, I recently initiated Dresden U.Lab Hub and X Prize Think Tank Dresden, hoping that both may work as door openers into an uncharted yet fascinating future. As Jay observed, one should always go through doors that look like an interesting opportunity!

Ralf Lippold

Dresden, Germany

A Memorable Chemistry Final

There is only one final exam that i can date from my four years at MIT. In May of 1952, I took the final for organic chemistry, a course that I thoroughly detested. At that time, it took brute-force memorization to learn organic, for undergraduates were not yet taught to use basic principles to predict chemical interactions.

I was horrified to find that the final exam consisted of eight steps in a chemical process leading to synthesis of penicillin. I felt like a complete fool, for I had attended course lectures given by Professor John Clark Sheehan, who synthesized penicillin. In later years I would tell my students how important it is to understand what makes your professors tick, using my story as an example. My experience is burned in my memory, for I married my high school sweetheart on May 31, 1952. The organic final left me in very poor condition for the wedding, so I will never forget what Professor Sheehan did to me!

Your article about Professor Sheehan (“Solving the ‘Impossible Problem,’” July/August 2015) leads to questions. Sheehan apparently succeeded in the synthesis in 1956. So what process had he used in the 1952 exam? Did he then know the steps in the process but not how to achieve them? And if so, how could he have expected MIT undergraduates to give him the answers? If he did benefit from our answers, perhaps we should have been listed as co-discoverers of the synthesis process!

William L.R. Rice ’53

Fredericksburg, Virginia

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.