Mainframe Computers That Handle Our Most Sensitive Data Are Open to Internet Attacks

They’re the machines that won’t die. In the 1960s many airlines, banks, and governments began processing sensitive transactions using giant mainframe computers—and their descendants are still in use. Now it turns out these living dinosaurs of computing also have a very modern vice: they overshare on the Internet.

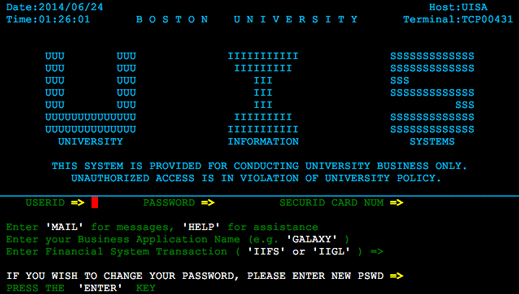

Security researcher Phil Young says he has found around 400 mainframes on the Internet offering up a login screen to anyone who connects. At the Security BSides conference in Las Vegas Tuesday he recounted how he had discovered mainframes belonging to the USDA, the National Institutes of Health, the state of New Mexico’s driver services database, South Carolina Health and Human Services, airline EgyptAir, and many university administration systems. He keeps a blog where software automatically posts screen shots of mainframe login screens found online.

Young found those mainframes by building on tools developed to scan the Internet for vulnerable software and devices (see “What Happened When One Man Pinged the Whole Internet”). He says what he found is concerning because although mainframes have evolved in many ways over the past 50 years, they lack modern security features needed for systems freely accessible over the Internet. And while mainframes handle precious data such as bank transactions and personal data, they are a small, specialized niche essentially invisible to the computer security industry that works to keep things like PCs, phones, and websites secure.

That means it’s likely that security flaws could be used to break into the mainframes that have blithely been put online, says Young. “There’s a false sense of security because people have been told for years that mainframes are secure,” he says. “But they’re not really secure—it’s only that no one cares about them.”

The accepted best practice for keeping software secure is for companies to publicly disclose newly discovered flaws in their products along with software patches to address them, as Microsoft does for Windows. That enables IT staff trying to keep many products up to date to know the risks they face and prioritize what to patch.

IBM does not use that model for its mainframe software, which dominates the market. It keeps details of security holes in its mainframe software secret, Young says, and privately contacts mainframe customers to say they should apply a new security patch, without saying exactly why.

“The security on this platform is not being managed well, and corporations and governments are using them for things that really matter to all of us,” says Young. “It’s this huge blindside waiting to happen.”

In response to a query about IBM’s security practices, a spokeswoman for the company said: “IBM’s mainframe is the most secure computer system in the world with unique cryptography technologies.”

There have been some recent examples of the dangerous consequences of attacks on mainframes and the critical data they handle. In 2014, a founder of Swedish file sharing service the Pirate Bay was found guilty of accessing a mainframe belonging to an IT contractor and accessing Danish government data including identification numbers and criminal records.

More recently, when leaders of the U.S. office of personal management appeared before Congress to explain how sensitive data on millions of federal employees was accessed by hackers, they pointed to decades-old code written in a programming language called COBOL. Invented in 1959, COBOL’s main use today is on mainframes.

Later this week at the DEF CON hacking conference, Young and a collaborator, Chad Rikansrud, will introduce several open-source tools to help security researchers probe mainframe software for security flaws that could be exploited. They hope to trigger a wave of scrutiny on mainframes, similar to what is now being applied to industrial control systems after the discovery of the Stuxnet attack on the Iranian nuclear program and Internet scans that found hundreds of thousands of vulnerable systems online (see “Protecting Power Grids from Hackers Is a Huge Challenge”).

Updated August 5, at 8.50 p.m. EST to add comment from IBM.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.