Robotic Surgery Linked To 144 Deaths Since 2000

Robotic surgeons were involved in the deaths of 144 people between 2000 and 2013, according to records kept by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. And some forms of robotic surgery are much riskier than others: the death rate for head, neck, and cardiothoracic surgery is almost 10 times higher than for other forms of surgery.

Robotic surgery has increased dramatically in recent years. Between 2007 and 2013, patients underwent more than 1.7 million robotic procedures in the U.S., the vast majority of them performed in gynecology and urology. “Yet no comprehensive study of the safety and reliability of surgical robots has been performed,” say Jai Raman at the Rush University Medical Center in Chicago and a few pals.

These guys set out to change that by analyzing records kept by the FDA, which has made it mandatory to report any incident in which a robotic procedure has gone wrong. This database is known as the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience, or MAUDE, and contains both mandatory reports and voluntary ones submitted between 2000 and 2013.

Raman and co found over 10,000 reports related to robotic procedures of which more than 1,500 described a significant negative impact for the patient. On average, this represents about 550 adverse events per 100,000 procedures.

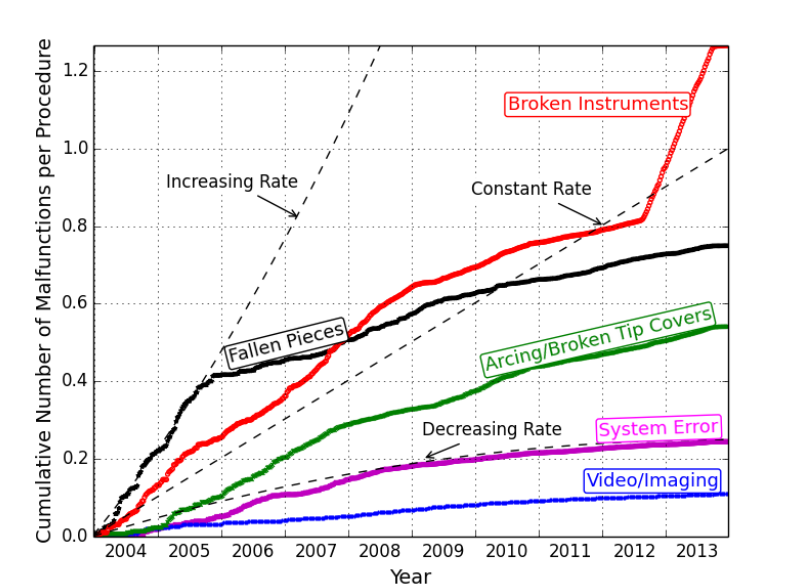

The number of robotic procedures dramatically increased during this period. And consequently the number of deaths and injuries has increased 30 times over since 2006. However, the number per procedure has remained more or less constant since 2007.

Raman and co say the types of adverse event fall into five categories. These include the equipment arcing or sparking during an operation, events that burned 193 patients between 2000 and 2013; in another category of incidents burned or broken pieces fell into the patient’s body, which occurred over 100 times and killed one patient; and another category involves uncontrolled movement of the instruments, which injured 52 patients and killed two of them. System errors such as the loss of video feed contributed to almost 800 other adverse events.

Curiously, although the database contains reports of 144 deaths during robotic surgery, the circumstances involved were recorded in detail in only a tiny fraction of cases. However, over 60 percent of these incidents were caused by device malfunctions while the rest were caused by factors such as operator error and the inherent risks of the surgery.

The fact that some forms of surgery are more risky than others is cause for concern. “The higher number of injury, death, and conversion per adverse event, in cardiothoracic and head and neck surgeries, could be indirectly explained by the higher complexity of the procedures, less frequent use of robotic devices, and less robotic expertise in these fields,” say Raman and co.

That may not reassure potential patients. Neither will the fact that the way the FDA collects this data means that these numbers almost certainly underestimate of the true death and injury levels.

That’s an interesting study that provides pause for thought for anyone about to undergo robotic surgery. The vast majority of these procedures take place without any adverse incidents. But Raman and co show that a significant proportion do suffer some kind of problem, even if it doesn’t lead to injury or death. “Device and instrument malfunctions have affected thousands of patients and surgical teams by causing complications and prolonged procedure times,” they conclude.

What Raman and co don’t discuss, however, is how these injury and death rates compare to procedures that take place without robotic techniques. Without that info, it’s hard to decide whether robots are making things better or worse.

Nevertheless, there is room for improvement. “Improved accident investigation and reporting mechanisms, and safety-based design techniques should be developed to reduce incident rates in the future,” say Ramon and co.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1507.03518: Adverse Events in Robotic Surgery: A Retrospective Study of 14 Years of FDA Data

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.