Could This Machine Push 3-D Printing into the Manufacturing Big Leagues?

The inventor of a new kind of 3-D printer says his research group will build a massive machine capable of mass-producing competitively priced plastic parts within two years.

Making plastic parts layer by layer according to digital instructions is a very slow process compared with conventional methods. That’s why additive manufacturing–or 3-D printing, as it is more popularly known–has thus far been economical only for making small batches of niche products like dental implants and hearing-aid shells. The new technique could increase the number of parts that can be made economically this way from thousands to millions at a time, at least for small, complicated objects.

Compared with conventional technologies like injection molding, additive manufacturing could significantly reduce material use and eliminate the costly machine tooling needed to make certain complicated shapes. It also makes it more practical to design unique architectures for parts that, for example, could help make automobiles and aircraft lighter and more fuel-efficient (See “10 Breakthrough Technologies 2013: Additive Manufacturing”).

Neil Hopkinson, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom, has been developing the new method, called high-speed sintering, for over a decade.

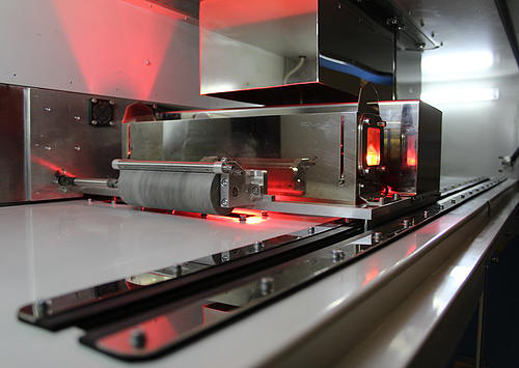

Laser sintering machines build objects by using a single-point laser to melt and fuse thin layers of powdered polymer, one by one. Hopkinson replaced the laser system, which is both expensive and slow, with an infrared lamp and an ink-jet print head. The print head rapidly and precisely delivers patterns of radiation-absorbing material to the powder bed. Subsequently exposing the powder to infrared light melts and fuses the powder into patterns, and the machine creates thin layers, one by one—similar to the way laser sintering works, but much faster.

Hopkinson’s group has already shown that the method works at a relatively small scale. They’ve also calculated that, given a large enough building area, high-speed sintering is “on the order of 100 times faster” than laser sintering certain kinds of parts, and that it can be cost competitive with injection molding for making millions of small, complex parts at a time, says Hopkinson. Now the group will actually build the machine, using funding from the British government and a few industrial partners.

High-speed sintering has the potential to be “very quick,” and the process could end up being much cheaper than laser sintering in certain cases, says Phil Reeves, the vice president of strategic consulting for Stratasys, a leading maker of many kinds of additive manufacturing machines and materials. However, a lot of work is still needed to develop materials that can work with the process if the goal is to compete with injection molding, he says. Judging from what Hopkinson has made public, the range of polymers that work with high-speed sintering is limited compared with that of injection molding, Reeves says, and many industrial polymers may not be compatible with the process, since it relies on combining the powder with an additional, light-absorbing material.

Another potential challenge to the commercialization of Hopkinson’s technology, says Reeves, is that Hewlett-Packard is developing a very similar technology. Though few details are known about HP’s system, called Multi Jet Fusion, it’s clear that it also employs an ink-jet print head that can deliver both a radiation-absorbing material and another material it calls a “detailing agent.”

For what it’s worth, Hopkinson’s high-speed sintering is patented, and the intellectual property is owned by Hopkinson’s previous institution, Loughborough University, which has licensed the technology to several entities, including the German 3-D printing company Voxeljet. Hopkinson says the machine his group is building now will be able to deliver additional materials, such as conductive inks used to print electronic devices, which remains a big technical challenge for additive manufacturing. “I don’t believe that HP plan on this,” he says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.