When I found out I’d gotten into MIT, I was bubbling with idealism. MIT was going to be AWESOME. Everything was going to be AWESOME. I was going to double-major in biological engineering and neuroscience and double-minor in history and music and I was going to UROP and I was going to be a Medlink and an MIT blogger and then become a doctor. I was going to rock out at my classes and a bazillion activities.

This, my friends, is what we call “froshy.”

But I didn’t understand what I was walking into when I left the impossibly sunny Los Angeles for the land of snow and science.

And that’s where it all went downhill.

When I arrived at MIT, I was ready to dive into all the amazing things I’d read about that made it sound like Hogwarts—the hacks, the toy design class, the roller coasters built by students. But instead, I was lonely. And I started struggling in classes. The Rocky montages I’d been dreaming about, where I would work late into the night and emerge at dawn an expert in organic chemistry, were replaced by endless nights with none of the romanticism and all of the self-doubt. Convinced that I had to be at the bottom of my class, I wondered if I was good enough to be here.

Like most freshmen, I had begun the painful process of defroshing. I learned that, no, I was not going to design robots every evening and build roller coasters every weekend and then graduate with a 5.0 in a double major and double minor. It turns out things take time, and people need sleep. Suddenly everything on the Admissions blogs felt like a lie—where were my excellent stories of triumph, where was the quest for truth that would define my every moment at MIT? I was worn out and sleep-deprived and miserable. MIT’s classes weren’t perfect, the tutoring resources weren’t great, and it felt as if parts of the administration were determined to take away the very things about MIT that were special, in some sort of bizarre effort to make it like every other school. This was mentally exhausting and very confusing.

And it’s this experience that turns the idealistic MIT frosh into a bitter MIT senior.

This well-known progression is treated as a fact of life. From the first day of MIT, you’d hear older students constantly snarking about the gauntlet we were running and how jaded they were becoming. It was a point of cultural pride, some sort of sign that you had grown up. Even though I fought it for so long, I couldn’t help but feel bitter by the end of my time at MIT. And that’s where this story ends.

Except it’s not. It’s just where students see it end.

I graduated and started living the bizarre phase known as “the rest of my life.” And something remarkable happened.

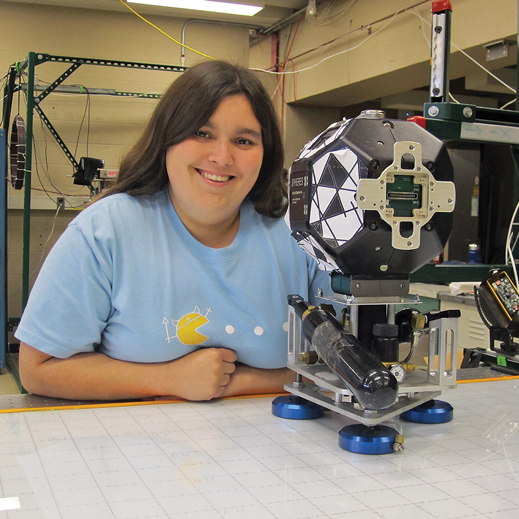

My burnout started fading, and with it my bitterness. I started looking back at all the things I had done at MIT—building robots, writing code that actually ran on a robot in the International Space Station, playing with lasers, learning to scuba-dive. I remembered late nights talking with hall mates about what it all means (sometimes “it” was life, and sometimes “it” was differential equations). Suddenly I started appreciating the experience, in a process that I half-jokingly call refroshing. I was finding the land between idealism and cynicism, in a place where wisdom gives birth to optimism.

MIT changed the way I live my life. I constantly seek what’s interesting, with a too-packed schedule that somehow seems easy because my days are nowhere near as crammed as they were at MIT. I know better than to think I want that experience again anytime soon, but I can now appreciate what it meant as a whole. I’m doing things that matter to me at a breakneck pace, and I couldn’t be loving life more.

MIT wasn’t what I expected, but it pushed me to be better than I ever thought I’d be.

Melissa Hunt ’13 (better known as Piper) is a software engineer at Akamai Technologies and spends her spare time in the air in a Cessna 172. She first wrote about the concept of refroshing in an MIT Admissions blog post.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.