Speeding Up 3-D Printing

3-D printers can make objects that are impossible or expensive to make with molding, milling, and other conventional manufacturing processes. However, these printers work too slowly to be widely used in factories.

That’s because today’s version of the technology builds up objects one layer at a time. It’s essentially 2-D printing over and over again, says chemical engineer Joseph DeSimone, founder and CEO of Carbon 3D, a startup in Redwood City, California. His company claims to have a technology that is 25 to 100 times faster, depending on the object and the material.

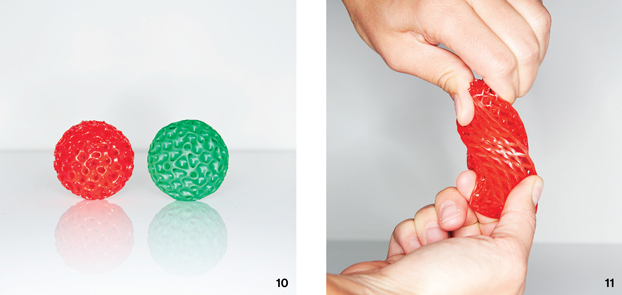

DeSimone hopes Carbon 3D’s printers will be used to make airplane or car parts that are stronger and yet lighter than ones used today, helping to reduce fuel consumption. He also wants to make it possible to rapidly print custom shoe soles, fitted to the quirks of individual arches, and place printers in operating rooms to generate stents matched to patients’ arteries.

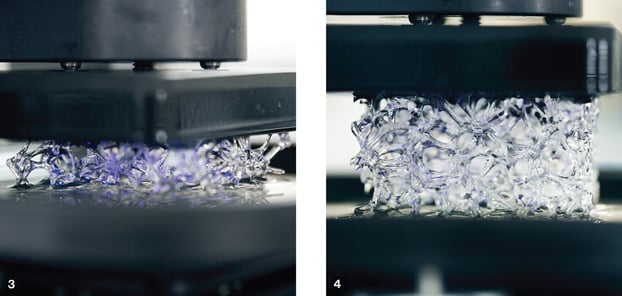

8. This is an enlarged model of the structure of bone. A pattern like this can’t be made using a mold, and it would be very involved to make by milling away material from a solid polymer block.

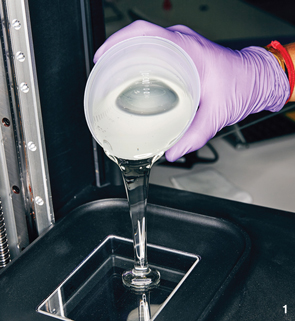

Carbon 3D’s process is a variation on a method called stereolithography, which uses projected patterns of ultraviolet light to catalyze the formation of solid polymers from a pool of resin. Stereolithography is typically a stop-and-start process—the object being printed sticks to the bottom of whatever vessel it’s in and must be pried off after each flash of light. Repeating this process with each layer is slow and leaves the completed object mechanically weak where each layer connects to another.

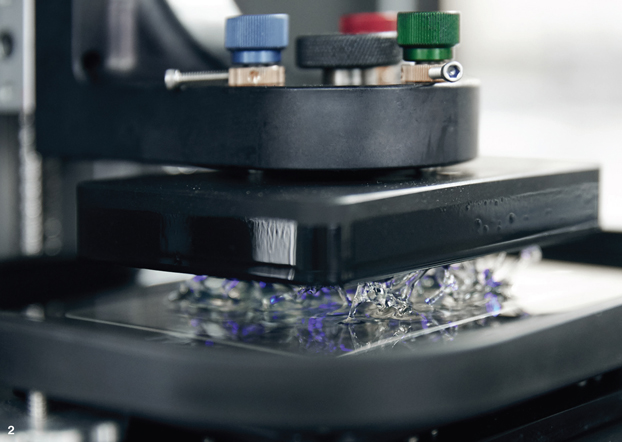

In Carbon 3D’s version, the pool of liquid resin sits in a vessel with a window at the bottom. The window is permeable like a contact lens, so it lets in not only light but also oxygen—which inhibits the chemical reaction just enough to prevent the polymer from solidifying on the bottom. That allows Carbon 3D to continuously print one layer on top of the next, which makes the process much faster and the resulting materials stronger, says DeSimone. “It looks like something growing out of a puddle,” he says.

Other researchers have demonstrated printing systems that incorporate some of the techniques used in Carbon 3D’s machines, and some of these methods can print features with higher resolutions than the company’s process. DeSimone, who founded Carbon 3D in 2013 and is on leave from the University of North Carolina to work at the company, has $51 million in funding to further develop the printers and polymer materials that will be its first products. This March, the company came out of stealth mode with a Science paper describing its technology and a captivating video of a small blue model of the Eiffel Tower emerging rapidly from a viscous little pool.

DeSimone says that while most commercial 3-D printing systems have been designed by mechanical engineers, his chemistry focus sets Carbon 3D apart. “We want to offer materials properties that haven’t been seen before,” he says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.