Smartphones (and Motorcycles) Fuel Hyperlocal E-Commerce in India

The heat wave gripping India on a day in late May feels particularly intense in the booming Delhi suburb of Gurgaon. Temperatures have soared to 109 °F by 12:30 p.m., and they aren’t done rising. Lizards are looking for shade. A profusion of new office parks, roads, and malls has obliterated any vegetation that might have preserved a little of the previous night’s coolness. And yet Albinder Dhindsa is smiling as he looks out his window, because this sort of weather is perfect for business.

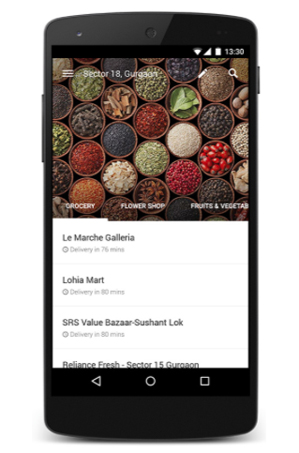

Dhindsa runs Grofers, a fast-growing online retailer that delivers groceries and other everyday goods within 90 minutes of an order. His customers: anyone who hates the hassles of running errands in noisy, crowded (and hot) Indian cities. The deliveries are made by motorcyclists who regard 75 cents per dropoff as decent pay. In the background, sophisticated information technology creates all the necessary connections between bikers, customers, and merchandise.

Grofers’s timing couldn’t be better. India’s strong economy the past five years has widened the middle class, whose engineers, accountants, and corporate managers will gladly spend money in the name of convenience and comfort. Let the rich hire servants; now anyone with the right mobile app also can do fewer fatiguing chores.

“India has been on the verge of something spectacular in e-commerce for God knows how long,” says Punit Soni, chief product officer for Flipkart, one of India’s largest online retailers. “Now, 120 million Indians have smartphones, and in a couple years it will be 600 million. As people access information, and try to buy stuff, use cases for e-commerce explode.”

Venture capitalists such as Shailandra Singh, head of Sequoia Capital India, have been bankrolling a variety of companies that use digital technologies and legions of couriers on Hero and Bajaj motorbikes to do what Amazon.com, to name one important rival, is still struggling to do: make ultrafast deliveries possible in India’s tumultuous cities. India’s hyperlocal online retailers don’t need to build their own big warehouses, Singh points out. Instead, they tap into India’s endless network of mom-and-pop stores, treating these retailers as mini-warehouses that are situated within a few minutes of online customers’ homes. The merchants use their smartphones to convey inventory updates; meanwhile dispatchers rely on cell phones to keep track of couriers and to improvise last-minute substitutions or refunds if available goods and customers’ requests don’t quite align.

Grofers was founded barely 18 months ago by two globally minded logistics engineers in their mid-30s: Dhindsa and Saurabh Kumar. (The company’s vivid orange packaging is a salute to the school colors of the University of Texas, where Kumar got a master’s degree in 2007.) A year ago, Grofers was handling 3,000 orders a week, all in the Gurgaon-Delhi region. Now Grofers is in the midst of expanding into eight other cities and is processing as many as 6,000 orders a day.

“We can’t get cardboard boxes fast enough,” Dhindsa says as he shows me around Grofers’s ground-floor loading dock. Upstairs, Grofers managers are scrambling to hire enough bike drivers and phone-support specialists. A year ago, Grofers had four software engineers, and now the company has 20. Dhindsa still needs more. On one recent Sunday, Dhindsa adds, customers in the Delhi area ordered so many tomatoes that many of his regular 860 supplying stores ran out. Grofers now independently buys six tons of produce in Delhi every day.

Grofers isn’t profitable yet, Dhindsa says, but he thinks the company could break even as average order size increases. Merchants grant Grofers a discount of about 10 to 12 percent on produce and about 6 percent on packaged goods such as soaps, diapers, and body lotion. But currently the average order is around 400 rupees ($6.50), with small orders from first-time shoppers keeping that figure low.

Indian shoppers have greeted Grofers with lots of enthusiasm and occasional grumbles. The service overall gets a healthy four-star rating out of five in Google’s app store, with about 70 percent of reviewers praising the company’s speed and convenience. (“They hop the shops for you,” one fan wrote.) Hardly anyone awards middling reviews. But about one-seventh of the reviews are sharply negative, one-star assessments, mostly because of order delays or cancellations.

Dhindsa says he constantly wrestles with how rapidly he should let Grofers expand, given that customer demand can come in unmanageable torrents. Many of the merchants in Grofers’s network are mom-and-pop stores operating in as little as 200-square-foot sites. Such retailers have some software to track inventory and sales, but updates may occur only weekly. Usually, out-of-stock issues can be resolved with a courier’s visit to a second store, or a minor adjustment in size or brand, according to Dhindsa, but about 6 percent have more serious snarls.

Some e-commerce entrepreneurs in India originally tried to create separate warehouses and logistics systems in the way that Amazon.com has done in the U.S. and Europe, but Rohit Bansal says he saw a better approach during a 2011 visit to China. Bansal, founder of one of India’s largest e-commerce companies, Snapdeal, noted that China had many online services serving as marketplaces for existing physical stores. “I came back convinced that everyone in India had been getting it wrong,” he says. “They were trying to do what Amazon did in the U.S. in the 1990s.” Bansal says Snapdeal is likely to launch its own version of a fast-delivery service in urban markets later this year, though he wouldn’t specify how sizable that initiative might be.

Never count out Amazon. Its operations outside the United States lost $76 million in the first quarter of 2015, but chief financial officer Tom Szkutak sees India as an eventual bright spot. “We’re super-excited from what we see there right now,” he told investors in April. “We’re investing appropriately for that opportunity.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.