How Mobile Phone Data Reveals the True Toll of Mass Layoffs

When it comes to understanding the mass behavior of individuals, mobile phone data is something of a gold mine. In recent years, researchers have used it to study commuting behavior, food consumption patterns, and even reproductive strategies in large populations of people.

Today, Jameson Toole at MIT and a few pals go further. These guys use mobile phone data to study the economic and personal impact of mass layoffs from a car parts factory in Europe. “We observe significant declines in social behavior and mobility following job loss,” they say.

They point out that insight at this level could revolutionize the ability to monitor economies by providing detail that is almost impossible to gather using conventional economic monitoring tools. And that could help decision makers put in place strategies that mitigate some of the devastating effects of unemployment.

In December 2006, the closure of a car parts factory in a small town in an undisclosed European country led to job losses for 1,100 workers in a town of only 15,000 people.

To study the impact of this closure, Toole and co analyzed the mobile phone records from a service provider with a 15 percent market share. These records spanned a 15-month period between 2006 and 2007 and included the anonymized caller IDs of each caller and callee, the location of the tower through which the call was routed, and the time of the call.

They also used call records from randomly chosen callers around the country as a control.

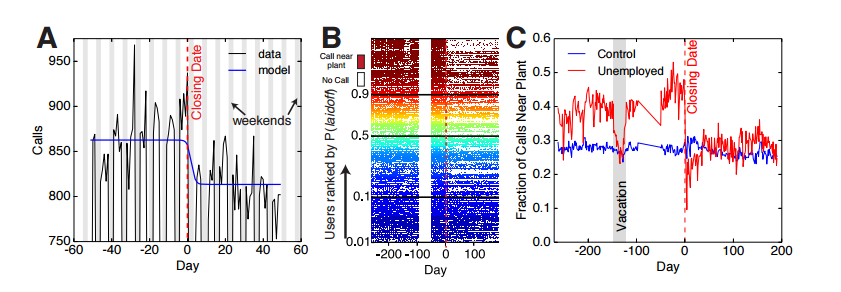

This data clearly shows the impact of the factory closure. The team examined the calls made in the area by almost 2,000 people during this period and found a sharp drop in the volume at the exact time of the closure, as verified by newspaper reports.

Of course, some people’s call records were unaffected by the closure and the team assumed these were individuals who had not been laid off. That allowed the team to separate these people from those assumed to have been laid off and to study each group in more detail.

This revealed significant changes in the behavior of people who had been laid off. These people made fewer calls, called a smaller percentage of their original network of contacts and traveled shorter distances.

“These results suggest that a user’s social interactions see significant decline and that their networks become less stable following job loss,” says Toole and co. “This loss of social connections may amplify the negative consequences associated with job loss.”

That’s an important insight into the impact of unemployment not just on the economy but on the lives of real people. A key point here is that this process can easily become part of the standard armory that economists use to understand the economy on a fine-grained scale that has never been possible before.

The standard way that economic agencies gather data is by surveys. These are complex, time consuming, and expensive to collect and provide only a broad brush picture of the way the economy is behaving. By contrast, mobile phone data has the potential to provide high resolution data almost in real time.

But this kind of analysis has downsides too, warn Toole and co. One problem is that researchers cannot choose the data they collect or how it is selected. What’s more, the data comes only from mobile phone users who themselves are a subset of the population that may be biased in various ways.

Nevertheless, mobile phone data is set to play an increasingly important role in how economists and computational sociologists understand the economy, the structure of the societies within it and the behavior of the atoms of society, the people who make it up. And perhaps it will allow decision makers to help these communities and the people devastated by sudden unemployment.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1505.06791 : Tracking Employment Shocks Using Mobile Phone Data

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.