An Algorithm That Can Help Robots Walk Off Injuries

Robots like the Mars Rover can operate on their own in harsh environments, and new research shows they could get even more self-sufficient by coming up with ways to adapt and keep moving after an injury.

The work is the subject of a study, published today in Nature, by researchers at Pierre and Marie Curie University in France and the University of Wyoming. The idea is that if robots are going to take on dangerous, difficult jobs, then they are going to have to cope with broken parts and injuries while out of reach of a human repair crew.

For instance, if a robot is sent on a search and rescue mission in the wake of an earthquake, it may need to cope with unexpected damage to one of its legs while surveying a collapsed building.

“The main challenge was to make something that learns, but learns in a few minutes,” says coauthor Jean-Baptiste Mouret, now a researcher at French innovation consortium Inria. In a video accompanying the paper, researchers show a spider-like robot that suffers an injury to one of its six legs. The creature starts trying new ways of moving, and in about 40 seconds regains 96 percent of its speed, looking less like a broken toy and more like a wounded animal crawling away.

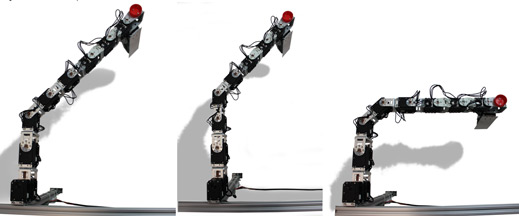

In another example, researchers damaged one of the motors on a mechanical arm. In less than a minute the simple robot figured out how to compensate for the broken joint and correctly place a ball inside a can.

Coauthor Antoine Cully, a PhD student at PMCU, notes that the robots learn with an “evolutionary algorithm.” This means that it will run repeated trial and error steps—building on a list it created before being deployed that details the things it can do and how valuable each one is—to determine a new way to get around. It’s like a simplified version of what humans do: if you sprain an ankle, you use memory and experimentation to figure out how to hobble around in the most efficient and least painful way.

Most robots don’t have such contingency plans, since they are typically programmed to move in specific patterns. If they are damaged, they may need to learn a new method of locomotion to maintain their functionality. In the study, Mouret says, the robots did not understand what was wrong with them; researchers didn’t try to anticipate anything about the damage they would sustain.

Of course robots, like cars, may have sensors that point out specific problems. But sensors won’t fix the problem, and Mouret says the objective was to learn without sensors (though the six-legged robot did use a Kinect to give it a baseline understanding of when it was upright and balanced). Also, Mouret points out that sensors can be wrong or, perhaps, not completely right. So the researchers’ theory, for now, is that a robot is better served figuring out the best way to move around through experimentation rather than sensor data.

“We want to incorporate this knowledge, but we have to be careful,” Mouret says.

It’s not yet clear how damaged a robot could be and still recover some movement, and researchers’ examples are still far from real-world scenarios such as fighting fires or rescuing people. Mouret says they will soon test these learning algorithms outside the lab on bigger robots.

And while watching the six-legged robot figure out a new method of movement inevitably brings about visions of the Terminator and evil robots, Mouret says researchers have plenty of time to build in proper safeguards to prevent robots from implementing behaviors that could harm people.

“Almost all animals are built to adapt to a small injury,” he says. “That doesn’t mean they want to take over the world.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.