A Prototype Battery Could Double the Range of Electric Cars

An experimental lithium-ion battery based on materials developed at a U.S. Department of Energy lab stores twice as much energy as the batteries used in most electric cars.

If the technology can be commercialized, it could give affordable electric cars a range of over 200 miles per charge, says Hal Zarem, CEO of Seeo, a startup that’s working on the technology. Today the cheapest electric cars, which cost around $30,000, typically have a range of less than 100 miles.

Alternatively, the improved storage capacity could be used to cut the size of battery packs in half while maintaining the current driving range, making electric vehicles considerably cheaper. A conventional battery pack with a range of 100 miles costs roughly $10,000.

Seeo, which is based in Hayward, California, recently raised $17 million from investors, including Samsung Ventures. It plans to start shipping batteries to potential customers for evaluation next year.

Seeo’s prototype is what’s known as a solid-state battery, meaning the liquid electrolyte used in conventional lithium-ion batteries is replaced with a solid one. Solid electrolytes have a number of potential advantages; the one Seeo has developed uses pure lithium, which allows it to store more energy. Other companies have developed batteries with solid electrolytes and pure lithium, but their energy storage capacity—at least for the large batteries needed in electric cars–has typically been less than what Seeo has achieved.

Normally, solid electrolytes don’t conduct ions as well as liquid electrolytes. Also, pure lithium tends to form metal filaments, or dendrites, that cause short circuits. That problem is usually prevented by incorporating the lithium into another material, such as graphite.

Seeo’s solid electrolyte, however, contains two polymer layers. One is soft and conducts ions; the other is hard and forms a physical barrier between the electrodes, to prevent dendrites from causing short circuits.

Other companies that have developed solid-state batteries with pure lithium have been forced to make changes elsewhere in the battery that decreased storage capacity, largely as a result of the voltage limitations of solid electrolytes. Seeo has been able to avoid that problem, though it’s not giving details.

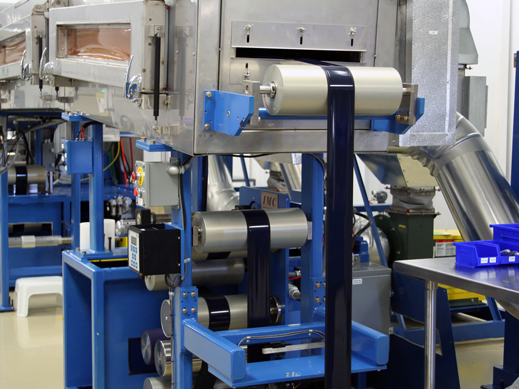

Zarem says the batteries can be made using conventional equipment for manufacturing lithium-ion batteries, which could help keep costs down.

Some key questions remain. Seeo doesn’t yet know how many times the batteries can be recharged, for example. In an ongoing test, prototype cells have so far survived more than 100 charges, but to be practical they will need to last over 1,000 cycles.

Another challenge is that existing lithium-ion batteries are quickly getting cheaper and better. By scaling up production of conventional batteries, Tesla Motors and Panasonic aim to produce electric cars that cost $35,000 and have a 200-mile range.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.