Brainstorming with Isaac Asimov

In 1959, I was working at Allied Research Associates in Boston when the U.S. military’s Advanced Research Projects Agency asked us for help. At MIT, two of our founders—Larry Levy, SM ’48, and Dan Fink ’48, SM ’49—had studied aerodynamic effects on structures. Now ARPA wanted their company to do two things: first, brainstorm new approaches to protecting the country from intercontinental ballistic missiles, and then conduct an engineering analysis to determine their feasibility. Bob Summers ’46, ScD ’54, would serve as the project’s principal investigator and Claude Brenner ’47, SM ’48, as its chief engineer. At my suggestion, we invited my friend Isaac Asimov, who was by then a well-known science fiction writer, to contribute to phase one of the endeavor.

I had met Asimov two years earlier, when I asked him to host monthly half-hour spots on Boston’s Channel 4 for the American Chemical Society. He was willing, but he warned me that he had no television experience. Although we rehearsed in the studio for an hour before each broadcast, his style was pedantic and scholarly, and the first few programs were not particularly successful. One day, however, the group ahead of us ran late, leaving Asimov no time to prepare. Forced to wing it, he was spontaneous and funny. Thereafter, we skipped rehearsals, and his programs were a hit.

As I got to know him, I found that while Asimov exuded self-confidence, he could be uneasy at times. He wrote about exotic transportation but would not fly on an airplane. He enjoyed bantering, and though he never drank, he could be extremely gregarious when he attended parties at my home. But sometimes in the middle of a party he would disappear into my library, and I would find him reading a book on science or the history of innovation. And despite his prominence as a science fiction author, he worried that his contract as an associate professor at Boston University would not be renewed because he hadn’t published in scholarly journals.

At the start of the ARPA project, Asimov sat in on a few meetings where lots of wild ideas surfaced. (I proposed establishing an explosive gas cloud above a city to blow up an incoming missile.) But as freewheeling as those discussions were, he clearly found the group format constraining and only occasionally contributed. Although he certainly could be creative, he had admitted from the outset that he knew nothing about the subject. And he did not like being expected to perform.

After several meetings, Asimov learned that he would need security clearance as the project proceeded. Having access to classified information would limit what he could write about, so he decided he should not continue. He felt obligated, however, to provide something useful to the group. So he retreated to his home-office loft, where he wrote at a desk in whose 10 drawers he stored all his manuscripts in progress. (Asimov did, in fact, sometimes work on as many as 10 books and articles at the same time; when he sat down to write, he would open the drawer containing whatever he felt most inspired to work on.) There, free of the constraints and distractions of a meeting, he penned “On Creativity,” the previously unpublished essay that I recently rediscovered in my basement.

Asimov wrote the essay to advise the Allied Research team on how to design meetings to draw out creative thinking. It’s as relevant today as it was then. “The world in general disapproves of creativity, and to be creative in public is particularly bad,” he wrote. Among other things, he advocated informality—using first names, joking, meeting over a meal instead of in a conference room—to “encourage a willingness to be involved in the folly of creativeness.”

Our meeting format, however, was dictated by ARPA. And in the cold, hard light of the conference room, we moved on to phase two of our project. Not a single idea survived. (My exploding gas cloud was rejected when someone pointed out that a missile would go through the cloud so fast that the explosion would occur behind it.) We concluded that there was no realistic way to defend against an intercontinental ballistic missile, but the U.S. military has spent well over $150 billion in the intervening 55 years to reach the same conclusion again.

When I unearthed Asimov’s essay, though, I remembered our project’s silver lining: it prompted one of the most imaginative writers of his generation to distill his thoughts on creativity.

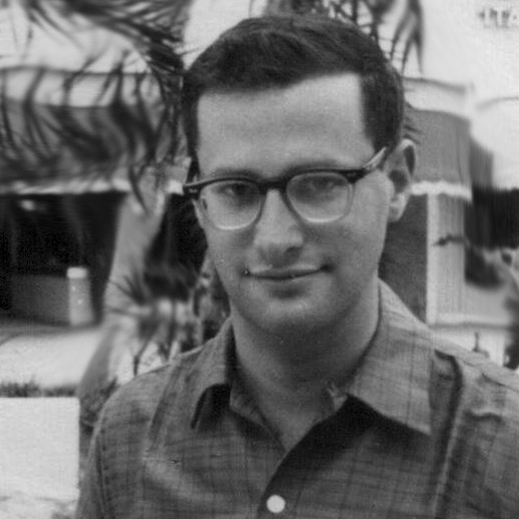

Arthur Obermayer, PhD ’56, is the founder and president of Moleculon Research, a chemical, polymer, and pharmaceutical R&D company, and the Obermayer Foundation. He was friends with Isaac Asimov for more than three decades.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.