The Coming Era of Egocentric Video Analysis

Head-mounted cameras are becoming de rigueur for certain groups—extreme sportsters, cyclists, law enforcement officers, and so on. It’s not hard to find content generated in this way on the Web.

So it doesn’t take a crystal ball to predict that egocentric recording is set to become ubiquitous as devices such as Go-Pros and Google Glass become more popular. An obvious corollary to this will be an explosion of software for distilling the huge volumes of data this kind of device generates into interesting and relevant content.

Today, Yedid Hoshen and Shmuel Peleg at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel reveal one of the first applications. Their goal: to identify the filmmaker from biometric signatures in egocentric videos.

One of the interesting features of egocentric videos is that the filmmaker never appears in shot. So whatever these videos show, there is always a question mark over who shot them.

That’s handy for people who want to broadcast their actions while maintaining their anonymity. For example, base jumpers who have trespassed may not always want to reveal their identity. And law enforcement officers can hide their actions by passing their cameras to colleagues.

The message from Hoshen and Peleg is that this kind of anonymity may not be as secure as some egocentric filmmakers had hoped. They point out that egocentric videos contain various important clues about the identity of the filmmaker, for example the height of the camera above the ground.

Some of these are unique, such as the gait of the filmmaker as he or she walks, which researchers have long known is a remarkably robust biometric indicator.”Although usually a nuisance, we show that this information can be useful for biometric feature extraction and consequently for identifying the user,” say Hoshen and Peleg.

The question these guys have set out to explore is whether these kinds of biometric indicators can be extracted from egocentric videos. They began with a two sets of egocentric videos, one showing a large amount of footage from just six users, and another of less footage of 47 different users.

Hoshen and Peleg say that the detailed content of this footage—the location, type of activity and so on—is not relevant for their task. Instead they focus on the optical flow in the videos—the pattern of motion of objects, edges and surfaces in the video from frame to frame. This can be extracted relatively quickly from sequences just a few seconds long.

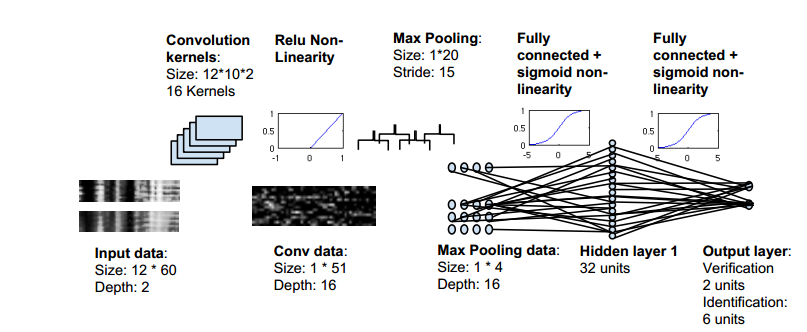

They used 80 percent of the data extracted in this way to train a neural network to spot the unique pattern of optical flow associated with each user. They then used the remaining 20 percent of the data to test how accurately the trained network could spot each individual filmmaker, while comparing the technique with other machine learning approaches.

The results show that filmmakers are usually straightforward to identify in this way and that the neural network generally outperforms other methods for analyzing the data. “Experimental evidence has confirmed that our method can determine user identity with high accuracy,” say Hoshen and Peleg. “The implication of our work is that users’ head-worn egocentric videos give much information away.”

That has some interesting consequences. One is that this kind of biometric identification could be used to prevent unauthorized use of these cameras. In other words, a camera could be programmed to work only when worn by a specific individual.

But there is another side to this work. This biometric approach could also be used to identify filmmakers who had otherwise hoped to keep their identity secret. “Care should therefore be taken when sharing such raw video,” warn Hoshen and Peleg.

Of course, it’s not hard to think up ways to beat software like this, perhaps by processing video footage in a way that changes the optical flow pattern without significantly changing the content. It may even be possible to tamper with an egocentric video to make it look as if it were filmed by another individual.

Hosen and Peleg say their approach is robust to some kinds of image stabilization processing. But the message from this kind of cat and mouse game is that anonymity is always going to be a slippery concept to maintain.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1411.7591: Egocentric Video Biometrics

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.