The Same Name Puzzle: Twitter Users Are More Likely to Follow Others With The Same First Name But Nobody Knows Why

Back in 1985, a Belgian psychologist called Josef Nuttin began asking students to pick out their favourite letter from a pair or a group of three. To his surprise, he found that people were more likely to pick letters that appeared in their own name. So a Fred is more likely to pick an F than an M and a Jennifer more likely to pick a J than an L.

Since then, the so-called name-letter effect has fascinated psychologists who claim to have found evidence of it in all kinds of diverse settings. Their work suggests that if something shares letters in your name, you are more likely to choose a brand, live in a city or even take a job.

Psychologists say the effect can be explained by the idea that people prefer situations that somehow reflect themselves, a phenomenon known as implicit egotism. But others have questioned the results, suggesting that the name-letter effect is a statistical artifact that would disappear if the numbers were properly accounted for.

Today, we get some new insight into this phenomenon thanks to the work of Farshad Kooti at the University of Southern California in Marina Del Ray and a couple of pals who have looked for evidence of the name-letter effect on Twitter and Google +. What they have found is surprising.

Kooti and co begin with a database of the 52 million Twitter users who joined the network before 2009 and the 1.9 billion links between them. They then filtered out all those who were not based in the US so as to avoid national biases.

Next, they picked the Twitter accounts belonging to a number of well-known brands, such as Sega, Nintendo, Pepsi and Coca Cola and analysed the followers, or a randomly chosen subset of 1 million of them, to see how many shared the same letters.

The results show little evidence of the name-letter effect. Of the eight brands they considered, three showed a statistically significant effect, three showed no significant effect and the remaining two had a negative name-letter effect. “The results suggest that the name-letter effect exists only in some special cases and it is not a generalizable concept for following brands on Twitter,” says Kooti and co.

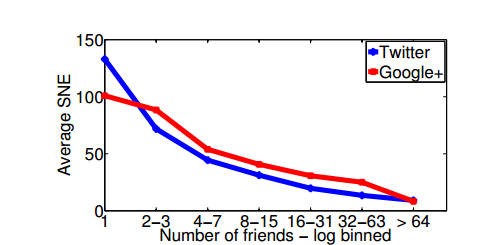

But they did find something else. Kooti and co also mined their database for evidence that people are more likely to follow others with the same first name. They looked at people with five popular names—Michael, John, David, Chris and Brian—and counted each time they followed other users with the same name.

The results were something of a surprise. Men are up to 30 per cent more likely than expected to follow somebody of the same name.

And the effect is even stronger among women with the most common names: Jennifer, Jessica, Ashley, Sarah and Amanda. In this case, women are up to 45 per cent more likely than expected to follow somebody of the same name.

That’s a curious discovery. Kooti and co say they’ve accounted for various biases, such as the possibility that certain first names are more popular among specific races and ethnicities or that people of similar age might have similar names and so on. In each case, the same-name effect remains significant. “We observe a robust effect, even when accounting for gender, age, race, and location,” they say.

For the moment, Kooti and co offer no explanation for why the name-letter effect is absent on these social networks while the same-name effect is so strong. Implicit egotism could be an answer but nobody is sure. Suggestions, please, in the comments section.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1411.5451 : The Social Name-Letter Effect on Online Social Networks

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.