Next-Generation Robot Needs Your Help

If you visit Manuela Veloso, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, you can expect to be met at reception, and led to her office, by an unfailingly polite and helpful assistant.

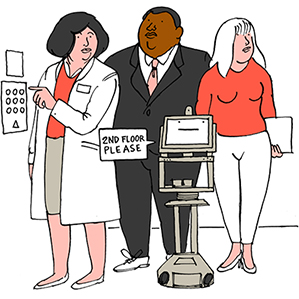

You might notice something a little odd about your chaperone, though, as it stops at the elevator and asks, in an electronic tone: “Can you press 7, and then press my ‘done’ button when we get to that floor?”

Your guide will be an unusual kind of robot, known as a Cobot, developed in Veloso’s lab. Resembling a laptop and a cluster of sensors sitting atop a wheeled barstool, it’s unlikely to be the most sophisticated robot you’ll ever encounter. It lacks arms, hands, or a particularly sophisticated vocabulary. But a Cobot employs a very simple and surprisingly effective trick to get around its inherent limitations.

Whenever it’s at a loss—when it needs to call an elevator, pick up an object, or find something that’s missing—it will simply pester the nearest human for help. If no one is nearby, a Cobot will send out an office-wide e-mail asking for help.

“I have been in the autonomy business for a long time,” says Veloso. “It’s very hard to be able to program a robot to be able to understand any speech or grab any object, even if they have arms. So I decided for them to be fully autonomous they have to be in an ‘asking for help’ mode.”

Several of Veloso’s Cobots roam Carnegie Mellon’s computer science department, ferrying packages between labs and offices, and dutifully showing guests around. Together they have performed tens of thousands of hours of useful service.

The robots may seem quirky, even a little annoying (Veloso admits that people occasionally get irritated by a robot’s neediness). But they also highlight how simple human-machine collaboration could enable robots to take on new roles in homes and workplaces. Programming robots to ask for help when necessary is far easier than giving them sophisticated language comprehension or skills in fine manipulation—incredibly difficult problems to solve.

“It is very good idea,” says Bilge Mutlu, an assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who researches the interaction between humans and robots. “It’s a lot more flexible and adaptable to day-to-day environments.”

Human-robot collaboration is already increasing in industrial settings (see “Increasingly, Robots of All Sizes are Human Workmates”). Finding ways for machines to collaborate in other settings could hasten the development of a new generation of service robot. “I am 100 percent sure that if people embraced robots with limitations we would have them in our homes as we speak,” Veloso says.

A few such robots are, in fact, already venturing into the real world. A robot called Tug, developed by Aethon, a company also based in Pittsburgh, moves equipment and supplies around a hospital. It doesn’t require the installation of any special beacons in order to navigate; if it gets stuck somewhere, it contacts a member of Aethon’s human support team, who will then remotely pilot the robot to its destination.

Veloso says the next generation of her Cobots will try to figure out for themselves when they might need assistance, instead of relying on a preprogrammed list of scenarios.

The usefulness of the Cobots suggests that the human-robot interface may turn out to be one of the most important areas for scientists and entrepreneurs to explore. “Even if we can’t achieve 100 percent autonomy,” says Mutlu, “we shouldn’t let that deter us from deploying autonomous systems.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.