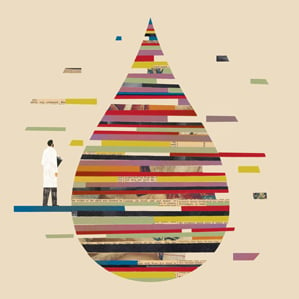

Scientists Pursue Novel Blood Tests for Cancer

The Hong Kong scientist who invented a simple blood test to show pregnant women if their babies have Down syndrome is now testing a similar technology for cancer.

Yuk Ming “Dennis” Lo says screening for signs of cancer from a simple blood draw could cost as little as $1,000. The test works by studying DNA released into a person’s bloodstream by dying tumor cells.

The idea is to create a cheap screening test that people might get annually at a doctor’s office to spot a tumor at its earliest stage, when it’s more easily treated. “It took 13 years to develop the prenatal tests, but the path was untrodden,” says Lo, who is based at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “Cancer will take a shorter time.”

The prenatal tests work by searching for fetal DNA present in a pregnant woman’s blood. Decoding that DNA can determine whether the baby has too many or too few chromosomes, problems that cause birth defects (see “Too Much Information”).

Both Lo and scientists at Johns Hopkins (see “Spotting Cancer in a Vial of Blood”) recently used a technique nearly identical to the one used in the prenatal tests to demonstrate that they could scan a person’s blood for evidence of genes that are duplicated, missing, or rearranged, something that is a hallmark of cancer cells.

But the testing strategy is very expensive. Tumor DNA is often present in tiny quantities if the cancer is at an early stage. It may account for just 0.01 percent of the DNA fragments in a blood sample. That means scientists end up decoding 9,999 bits of normal DNA for every stretch of cancer DNA they encounter. The result: building up a rough snapshot of the tumor’s genome using sequencing machines can cost $10,000 or more.

“It’s doable, but very expensive,” says Andre Marziali, chief scientific officer of Boreal Genomics, a startup developing cancer tests. “There is a trade-off between the breadth and the cost.”

Lo says he’s now developing a different way to measure DNA that could cut the cost of the cancer test by about 90 percent.

The new method looks for changes in methylation—a chemical modification to DNA that controls gene activity. The genes of cancer cells widely lose their methylation marks, a feature that Lo says can be reliably spotted using less sequencing.

Other scientists say Lo’s approach is not yet highly accurate and could incorrectly diagnose many healthy people as having cancer. Victor Velculescu, a genome scientist at Johns Hopkins, says such false positives are a problem for many screening tests. “Although the approach used by Dr. Lo is an excellent application of this technology, it would have the same hurdle to overcome,” he says.

Lo says he is testing his technique in Hong Kong by following 20,000 people at risk for cancer as part of a $4 million study paid for by the Hong Kong government. Many are infected with hepatitis B, a virus that can cause liver cancer and is carried by about 10 percent of the Chinese population.

Currently, Hong Kong residents infected with hepatitis B get ultrasound exams, which can also spot tumors fairly early. Lo says he hopes to determine if a DNA blood test is a better option.

Most scientists believe the path to an all-purpose cancer test isn’t yet clear, but the technology is evolving so quickly it seems certain it will be possible. “To make these tests something that anyone can have in the doctor’s office could be 20 years away, but that day is coming for sure,” says Marziali.

Lo licensed his patents on prenatal testing to a California company, Sequenom, which launched a pregnancy test in 2011. He says he hasn’t decided how to commercialize the cancer test yet.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.