Blame the Weather for Last Year’s Rise in U.S. Carbon Dioxide Emissions

A colder winter was one of the main reasons carbon dioxide emissions from energy use rose in the United States by 2.5 percent in 2013, according to new data from the Energy Information Agency. Besides a small rise in the price of natural gas and slightly cheaper coal, the weather played the biggest role in in pushing up emissions, the IEA says.

The new numbers show that fluctuations in weather patterns and relatively small changes in fuel prices are enough to counteract the emissions reductions that have resulted from greater solar and wind power capacity and increased use of cleaner-burning natural gas instead of coal.

Compared with 2012, there were 18 percent more days in 2013 cold enough to cause a spike in demand for energy for heating, says the EIA. This contributed to an 0.5 percent increase in the amount of energy used per dollar of GDP, bucking the trend seen from 2003 to 2012, when that ratio decreased by an average of 2 percent per year.

In addition, the amount of electricity generated using natural gas dropped 10 percent between 2012 and 2013, while coal generation increased by nearly 5 percent. The price of natural gas rose from $3.54 per million BTU in 2012 to $4.49 in 2013, while the price of coal dropped from $2.38 per million BTU to $2.35.

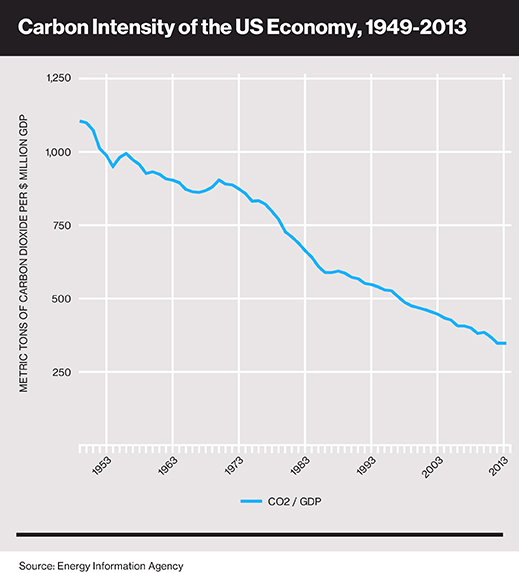

More coal and less gas meant a much smaller drop in the U.S. energy system’s “carbon intensity”—the amount of carbon dioxide emitted per unit of energy produced.

All of this combined to make the carbon intensity of the whole U.S. economy, or the amount of carbon dioxide emitted per million dollars of GDP, rise by 0.2 percent, the first such rise since the global recession, as shown in the chart below.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.