Synthetic Biologists Create Paper-Based Diagnostic for Ebola

James Collins, a synthetic biologist at Boston University, says he’s been able to print the ingredients for simple DNA experiments on paper, freeze dry them, and use them as much as a year later. It could lead to cheap diagnostic tests for viruses like Ebola.

The work, described this week in the journal Cell by Collins and colleagues from Harvard, could lead to bandages that change color if an infection is developing, environmental sensors worn on clothing, or cheap diagnostics for viruses like Ebola.

The idea of inexpensive paper-based diagnostics isn’t new. But so far, these tests have relied on traditional chemistry like pregnancy tests do (see “Super-Cheap Health Tests” and “Paper Diagnostics”). Collins says his work now extends the idea to precisely engineered genetic reactions.

The technology is an adaptation of a workhorse lab method known as a “cell free system,” in which the basic processes of a cell—such as reading a DNA strand to make a protein—are carried out in a test tube.

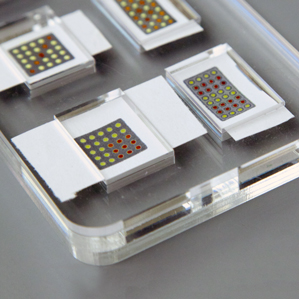

The advance Collins made was to embed cell-free systems onto porous paper. His team added some essential enzymes as well as specially designed genes that make proteins, but only if they’re triggered by a matching strand of DNA or RNA.

“It’s a pragmatic, very big-deal improvement,” says Julius Lucks, an assistant professor of chemical and biological engineering at Cornell University. “Now we can ask ‘What do we want to do [with it]?’ ”

Collins showed the system could detect the Ebola virus, whose genetic code consists of RNA. When his team added bits of Ebola RNA to paper test strips, the genetic material completed a “circuit” allowing production of a protein which stained the paper, causing it to turn dark purple in about an hour.

Using the paper tests still requires some lab expertise, for instance to first isolate the genetic material from a virus or bacterium. But Collins says the paper tests themselves are extremely cheap. He estimates that each detection strip would cost only between 4 and 65 cents, and could be designed and produced in a day or so.

“I think it’s very cool,” said Lingchong You, an associate professor of biomedical engineering at Duke University. “Conceptually, it’s extremely simple.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.