Lighting Sheets Would Use Half as Much Power as Lightbulbs

The next big thing in lighting could be glowing sheets that use half as much energy as an equivalent fluorescent fixture and can be laminated to walls or ceilings. The sheets will contain organic LEDs, or OLEDs—the same kind of technology used in some ultrathin TVs and smartphones.

OLEDs could be used in large sheets, because organic light-emitting molecules can be deposited over large surfaces. They also run cooler than LEDs, so they don’t require elaborate heat sinks, making a lighting structure simpler. OLED lighting is 10 to 100 times more expensive than conventional lighting, but as costs come down, it could eventually replace conventional fluorescent fixtures.

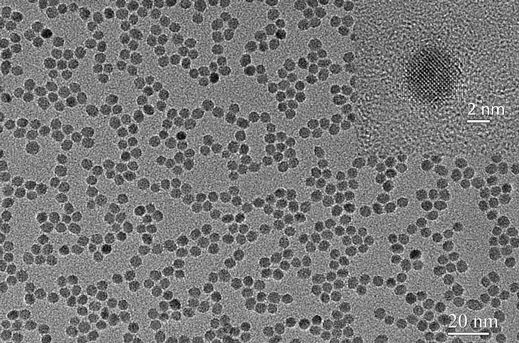

In recent weeks, researchers have announced advances that could greatly improve the efficiency of OLED lighting. For example, a startup called Pixelligent has found a way to double or triple the light output. It does this via nanoparticles that ease the transition for light as it passes between the parts of an OLED device. This prevents reflections and allows more light out.

Various companies are also making progress toward lowering costs. Konica-Minolta and OLED Works (a business formed from Kodak’s former OLED division) are both developing cheaper new manufacturing techniques. These companies, as well as the Dutch company Philips, plan to scale up production of OLED lighting in the next year or two, which should also lower prices.

OLED lighting is expensive in part because manufacturers typically use equipment developed for making high-resolution displays, says Michael Boroson, the chief technology officer of OLED Works. His company is reëngineering the equipment so it uses less material and works more quickly.

This fall, Konica-Minolta will start full-scale production of OLED lights on flexible plastic sheets. The company uses “roll-to-roll” processing, which should be faster and cheaper than making OLED lights in batches, as is done now. The factory will be able to produce a million 15-centimeter-wide panels per month.

Even with such advances, it will take years to bring costs low enough to make OLED lighting widely used. OLED lamps cost as much as $9,000 now. But, Philips aims to introduce OLED products by the beginning of 2017 that cost $600 to $1,600. Costs are expected to drop further as the scale of production increases.

Fundamental research could also make OLED lighting more realistic. OLED lighting blends red, green, and blue light, but the blue light is relatively inefficient. Last week, Stephen Forrest, a professor of materials science and engineering at the University of Michigan, published work on a more efficient, longer-lasting blue material that might solve this problem.

“OLEDs produce a beautiful sheet of light,” Forrest says. “I believe OLED lighting will be a very important lighting source in the future, perhaps a dominant one. But there’s a big gap between what we can do now and what we need to get costs down.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.