Relationship Mining on Twitter Shows How Being Dumped Hurts More than Dumping

“The breakup of a romantic relationship is one of the most distressing experiences one can go through in life.” So begin Venkata Garimella at Aalto University in Finland and a couple of pals, with more than a hint of misty-eyed regret. These guys have more insight than most thanks to their work studying the break-up of romantic relationships through the medium of Twitter.

As social media has permeated every aspect of daily life, its role in romantic relationships has become ubiquitous, as phrases such as “Facebook official” testify. But while the role of Facebook in relationships has been well studied, the part that Twitter plays is less well understood.

Today, Garimella and co put that right with the first comprehensive study of the way relationship break-ups are reflected in the Twitter stream. The results provide new insights into the psychological role of social media in relationship break downs and reveal an entirely new phenomenon of “batch unfriending” among people who break up.

To find couples who have broken up, Garimella and co began with a dataset of 80 per cent of all the tweets posted on Twitter during a 28 hour period in July 2013. They filtered this data looking for users who had mentioned another user in their profile along with words and phrases such as boyfriend, girlfriend, love, bf, gf, taken and so on. Their idea is that this pattern is indicative that two users are in a romantic relationship.

They removed from the resulting list all accounts mentioning other accounts of the same person on other services such as Instagram and Vine. They also removed accounts that mentioned celebrities such as @JustinBieber and @KatyPerry along with words like boyfriend or girlfriend, which seemed to imply some kind of one-sided, para-romantic relationship these personalities.

That left the team with almost 80,000 users (40,000 pairs) who appeared to be romantically linked. They followed the tweets from these couples between November 2013 and April 2014 and picked out all those whose romantic status appeared to have changed. “If they were in a relationship in November and not in April, we assume that the couple broke up sometime during this period,” say Garimella and co.

They pruned this further by filtering for English language users based in the US, Canada and the UK, so as to rule out misunderstandings in the data analysis that might arise from language or cultural issues. They also excluded married couples, since psychologists have long known that these relationships follow different dynamics. And they excluded people in same sex relationships for the same reason.

Finally, Garimella and co asked three human judges to read the original profiles and determine whether each of the remaining couples really were romantically linked. (They used an online crowdsourcing service for this). They included only those couples that all three judges agreed on.

That left 661 couples who appeared to have broken up during the study period. Indeed, Garimella and co were able to pinpoint the weeks during which the break up occurred by looking for the dates on which users removed their former partner’s name from their profiles.

As a control, the team also picked at random a further 661 couples who did not break up during the study.

Some of the results are unsurprising. For example, by searching the last 3000 or so tweets from all these users, Garimella and co were able to work out when most of the relationships began and so how long they lasted. It turns out that longer-lasting relationships are less likely to break down, something that psychologists have long known from real-world studies.

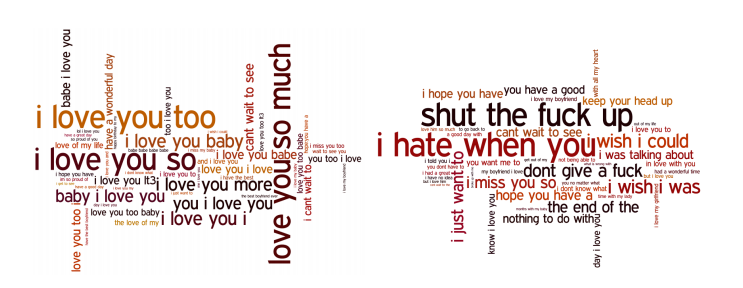

The team also studied how people’s profiles changed after their relationship broke down by counting the frequency of words used and how this changed. The top gainers were “im”, “god”, “don’t”, “live”, “single”, “dreams”, “blessed” and “fuck”. They created world clouds of the before and after world frequencies to highlight this difference (see picture above). “One story that potentially emerges from this is that people (i) become more self-centered, (ii) find stability in religion and spirituality, but also (iii) curse life for what has happened,” conclude Garimella and co.

They also studied the change in communication patterns between users who have broken up. Their finding is easy to sum up. “The change is roughly from “I love you so …” to “I hate when you …,” say Garimella and co, who were surprised by the public nature of the infighting that occurs post-break up.

More interesting is the clear change in pattern of communication that occurs before a break up. As a break up approaches, the number of messages to the partner decreases while the number of messages to other users increases. “These observations could potentially lead to “early breakup warning” systems,” they say.

But the most thought-provoking finding is the discovery of a process the team call “batch unfriending”. Garimella and co say there is clear evidence that after a break up, each partners’ number of friends and followers drops by around 15-20. In other words, there is a sudden change in each partners’ network of connections after the break up.

That’s something of a surprise. “After the breakup, we were expecting partners to potentially unfollow each other but, apart from that, we were expecting “business as usual” as far as the social network was concerned,” they say. The change is akin to a kind of earthquake in the social network—a sudden re-arrangement of links. Just why this happens so suddenly isn’t clear but is clearly an interesting topic for further study.

Garimella and co also found evidence for post-break up depression by analysing the language used in tweets. However, it is not clear whether the depression is the result of the break up or the cause of it. They also say that the person who initiated the end of the relationship, feels less depressed than the person who is rejected. In other words, being dumped hurts more than dumping.

That’s a fascinating insight into the death of relationships, as played out on Twitter. And it provides plenty of fodder for future work. For example, there is the body of work that infers personality traits of users based on their language usage. So one possibility would be to look for correlations between personality types and relationship break downs.

Then there is the strange world of one-sided para-relationships with celebrities, which also seem to break up like ordinary ones. Do these users also experience post-relationship blues? Justin Bieber and Katy Perry might be interested to know about the unintended consequences of their online fame.

Clearly there is plenty of low hanging fruit in the emerging world of relationship data mining.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1409.5980 : From “I love you babe” to “leave me alone” - Romantic Relationship Breakups on Twitter

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.