Cheap, Scratch-Resistant Displays

Glass touch-screen displays are easily cracked and scratched, making them a weak point in today’s ubiquitous mobile devices. Sapphire—which is about three times harder than toughened glass—could make such damage a thing of the past. Sapphire is already used on a few luxury smartphones and for small parts of recent iPhones, including the cover of the camera lens and thumbprint reader on the iPhone 5S. And some models of Apple’s newly announced watch include a sapphire face. In a sign of the material’s growing importance, Apple recently invested $700 million in a sapphire processing factory in Arizona.

The problem is that sapphire costs five to 10 times as much as the toughened glass used now in almost all smartphones, limiting its use to small screens or specialized devices. But in Danvers, Massachusetts, engineers at GT Advanced Technologies say they are solving the cost problem with a new manufacturing process that cheaply and efficiently produces sheets of sapphire just a quarter as thick as a piece of paper. These sheets, when laminated to a conventional glass display, can do a lot to prevent damage, since it only takes a very thin layer of sapphire to prevent scratches and to resist cracks when a phone is dropped.

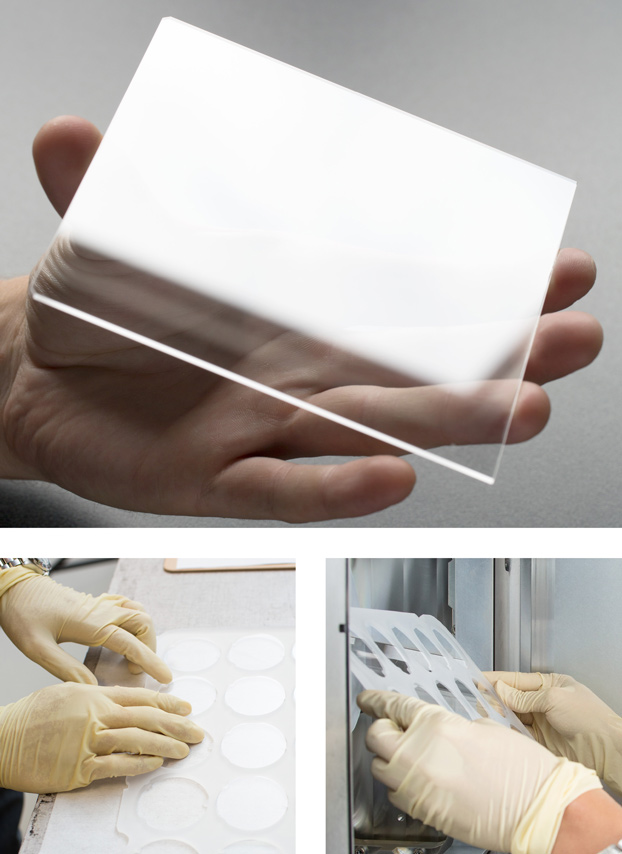

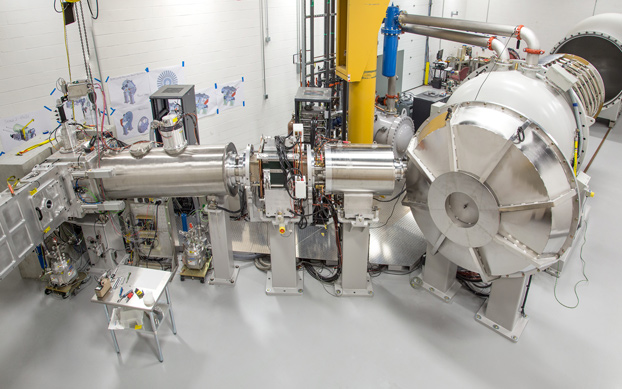

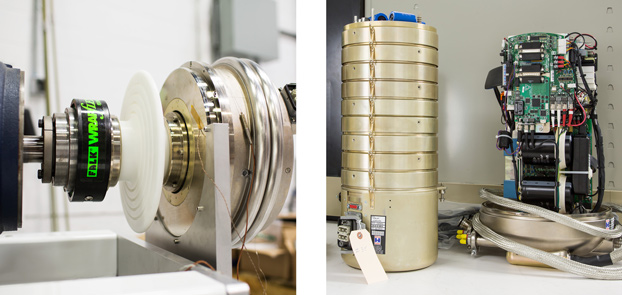

Left to right: A technician loads circular wafers of sapphire into a template, then loads that into a high-power ion accelerator.

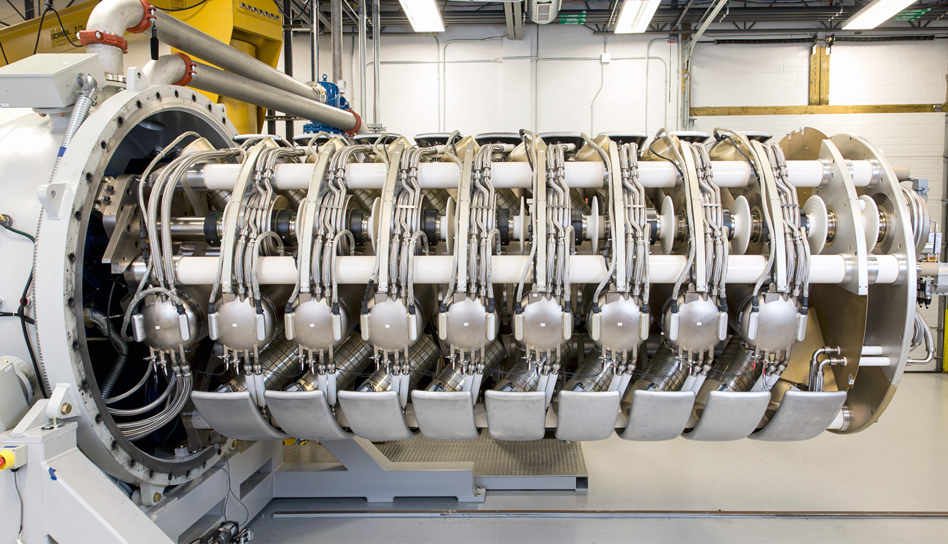

Left: One of the generators is tested.

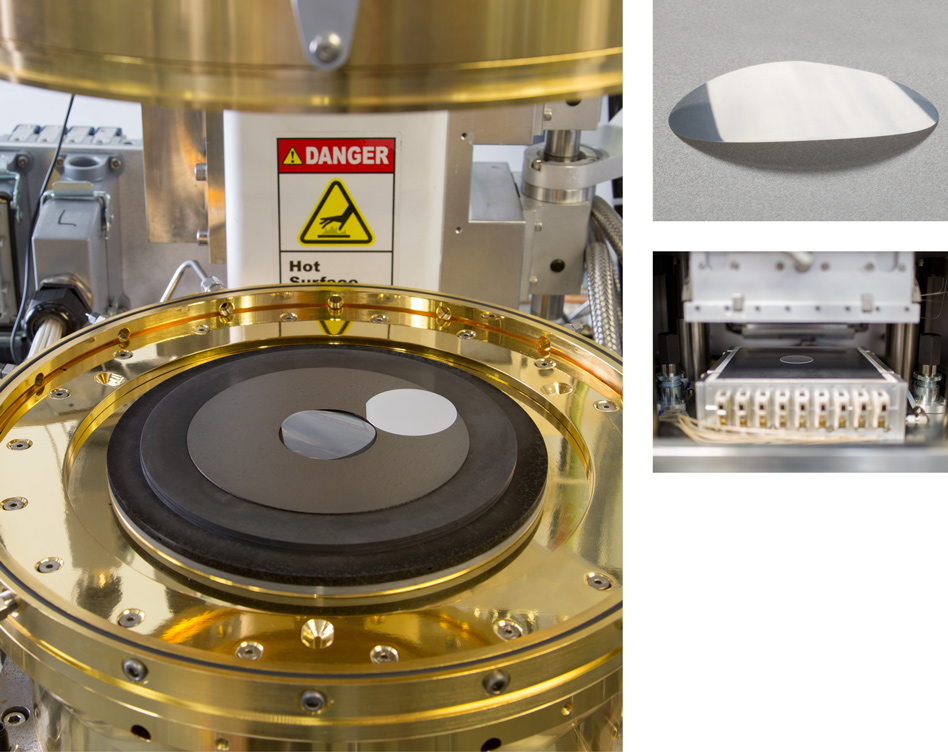

Center: A power supply converts low-voltage electricity to high-voltage.

Above top: The resulting sheet is just 26 micrometers thick.

Above bottom: A laminating machine affixes sapphire to glass.

The company’s process can make about 10 sapphire sheets from the same amount of material that would go into just one solid display. That could help make sapphire ubiquitous in smartphones. Indeed, it would probably only add a few dollars to the cost of a phone. And it could allow sapphire to be used on displays for larger devices, such as tablets.

GT Advanced Technologies is already a major sapphire supplier, having built the Arizona plant for Apple. The facility in Danvers is devoted to a next-generation manufacturing process. Behind the process is a machine called an ion accelerator, the size of a cement mixing truck. The machine generates two million volts of electricity and flings hydrogen ions at sapphire crystal wafers, embedding the ions at a precise depth in the sapphire. Then the material is heated in an oven, causing hydrogen bubbles to form within it and ultimately forcing a layer of sapphire to pop off. When that layer is polished, it becomes transparent.

Though ion accelerators are already used to modify the properties of semiconducting materials, GT Advanced Technologies had to develop a machine 10 times more powerful in order to embed ions deeply and precisely enough to produce usable sheets of sapphire. The method is a big improvement over conventional means of making thin sapphire sheets, which involve sawing up a large chunk of sapphire into wafers and then grinding them down. That process wastes costly sapphire and, at the same time, introduces defects that make the thin sheets easy to break.

Ted Smick, the company’s vice president of equipment engineering, expects his ion accelerator to be ready for market next year, after he develops an automated system for moving sapphire through the process. Eventually, the technology could help make sapphire-coated displays commonplace, making many of the hundreds of millions of smartphones sold each year far more durable.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.