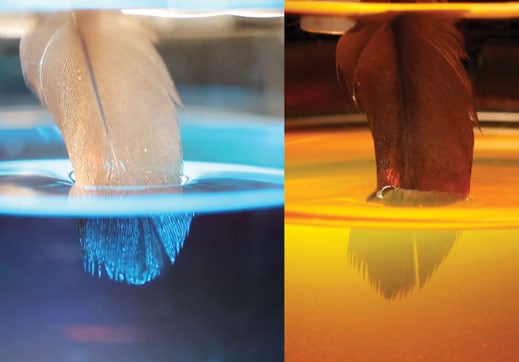

When diving birds resurface, water rolls off their feathers like, well, water off a duck’s back. That classic example of efficient water-shedding is made possible by both chemistry—the birds’ preening oil—and the microstructure of feathers.

New research, published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, reveals how diving birds can reach depths of some 30 meters without having water permanently wet their protective feathers.

Through lab tests and modeling, researchers from MIT and London’s Natural History Museum separated chemical and structural effects to show why the combination of surface coating and shape is so effective. They coated feathers from six types of diving birds with a layer that neutralized the effect of the preening oil and then recoated them with hydrophobic material, preventing variations in oil composition from affecting the results.

It had been known that during dives, feathers trap a thin insulating layer of air called a plastron, so water never comes into direct contact with the skin. The new work shows that beyond a depth of just a few meters that plastron collapses, letting water penetrate into the feather structures. The depth dependence of this phenomenon had not previously been known. “It’s an abrupt transition,” says chemical engineering professor Robert Cohen.

But once the protective air layer collapses, the preen oil prevents the water from penetrating the feathers’ barbs and barbules. Consequently, when the birds emerge from the water, “if a feather gets wet, there is no need for it to dry out, in the traditional sense of evaporation,” Cohen says. “It can dry by directly ejecting the water from its structure as the pressure is reduced when it comes back up from its dive.” The team refers to this as “spontaneous dewetting.”

But this process only works with water. If a feather is immersed in oil, as it might be after an oil spill, the feathers are fully wetted, mechanical engineering professor Gareth McKinley explains: “The thermodynamics show that if [feathers] get wetted by oil, they’re going to stay wetted, irreversibly, unless you steam-clean them or something.”

“Diving birds are only just adapted, partly through the microstructure of their feathers, to reach their maximum diving depths without suffering permanent effects,” says team member Andrew Parker of the Natural History Museum, which provided feathers for the research. “It is one of the most amazing examples of evolution and adaptation, with not a trace of overengineering.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.