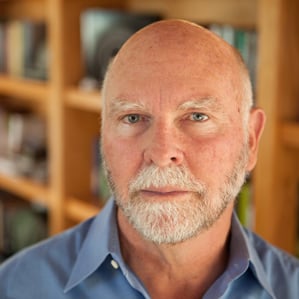

Three Questions for J. Craig Venter

Genome scientist and entrepreneur J. Craig Venter is best known for being the first person to sequence his own genome, back in 2001.

This year, he started a new company, Human Longevity, which intends to sequence one million human genomes by 2020, and ultimately offer Web-based programs to help people store and understand their genetic data (see “Microbes and Metabolites Fuel an Ambitious Aging Project”).

Venter says that he’s sequenced 500 people’s genomes so far, and that volunteers are starting to also undergo a battery of tests measuring their strength, brain size, how much blood their hearts pump, and, says Venter, “just about everything that can be measured about a person, without cutting them open.” This information will be fed into a database that can be used to discover links between genes and these traits, as well as disease.

But that’s going to require some massive data crunching. To get these skills, Venter recruited Franz Och, the machine-learning specialist leading Google Translate. Now Och will apply similar methods to studying genomes in a data science and software shop that Venter is establishing in Mountain View, California.

The hire comes just as Google itself has launched a similar-sounding effort to start collecting biomedical data (see “What’s a Moon Shot Worth These Days”). Venter calls Google’s plans for a biomedical database “a baby step, a much smaller version of what we are doing.”

What’s clear is that genome research and data science are coming together in new ways, and at a much larger scale than ever before. We asked Venter why.

How are we doing in genomics?

In my view there have not been a significant number of advances. One reason for that is that genomics follows a law of very big numbers. I’ve had my genome for 15 years, and there’s not much I can learn because there are not that many others to compare it to.

Why did you hire an expert in machine translation as your top data scientist?

Until now, there’s not been software for comparing my genome to your genome, much less to a million genomes. We want to get to a point where it takes a few seconds to compare your genome to all the others. It’s going to take a lot of work to do that.

Google Translate started as a slow algorithm that took hours or days to run and was not very accurate. But Franz [Och] built a machine-learning version that could go out on the Web and find every article translated from German to English or vice versa, and learn from those. And then it was optimized, so it works in milliseconds.

I convinced Franz, and he convinced himself, that understanding the human genome at the scale that we are trying to do it is going to be one of the greatest translation challenges in history.

How is discovering the connection between genes and disease like translating languages?

Everything in a cell derives from your DNA code, all the proteins, their structure, whether they last seconds or days. All that is preprogrammed in DNA language. Then it is translated into life. People are going to be very surprised about how much of a DNA software species we are.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.