Cheap and Nearly Unbreakable Sapphire Screens Come into View

This fall, rumor has it, Apple will start selling iPhones with a sapphire screen that is just about impossible to scratch.

The supposed supplier of that sapphire, GT Advanced Technologies, can’t confirm as much. But this week the company showed me a new manufacturing process that produces inexpensive sheets of sapphire roughly half as thick as a human hair, making it possible to add a tough layer of sapphire to just about any smartphone or tablet screen relatively cheaply (see “Your Next Smartphone Screen May Be Made of Sapphire”). The manufacturing technology, known as an ion accelerator, can make fine sheets of other costly materials, so it could also lead to better and cheaper electronics and solar cells.

Sapphire, or crystalline aluminum oxide, is made in nature but can also be manufactured. It is second only to diamond in hardness, although incorrect processing can leave defects that make it brittle. Because of its scratch-proof properties, it has long been used for making LEDs, sensors on missiles, and the screens on some high-end phones that cost as much as $10,000.

But sapphire has been too expensive for widespread use. A screen made entirely out of sapphire, as the forthcoming iPhone’s may be, remains five times as expensive as a regular one, or $15 to $20 each. But laminating glass with sapphire could bring the cost down to $6, according to estimates by Eric Virey, an analyst for the market research firm Yole Développement.

Smartphone makers have long taken advantage of advances in glass production to make devices with stronger and more durable screens. The most well-known of these screens is made from Corning’s Gorilla Glass, which is used in iPhones. But even Gorilla Glass is vulnerable to scratching and cracking, and replacing the glass is expensive.

The conventional approach to making sheets of sapphire is to saw a large crystal of the material—say 40 centimeters across—into wafers a few hundred micrometers thick. These wafers can then be made thinner, but that requires more sawing, and then grinding the sapphire down, which wastes huge amounts of sapphire.

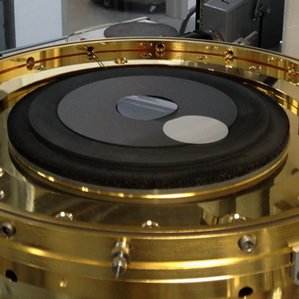

GT uses a different approach in its new machine, which is the size of a concrete-mixing truck and operates in its labs in Danvers, Massachusetts. The machine shoots hydrogen ions at a wafer of sapphire, implanting the ions to a depth of 26 micrometers. The wafer can then be removed and heated up so that the hydrogen ions form hydrogen gas, which expands and causes a 26-micrometer-thick layer of sapphire to lift off.

Ted Smick, vice president of equipment engineering at GT, says the next step is to engineer a system to automate the handling of sapphire wafers in a way that makes sapphire sheets at a fast rate. He estimates that designing and implementing such a process will take about nine months.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.