Researchers Test Personal Data Market to Find Out How Much Your Information Is Worth

The personal information that your smart phone can collect about you is increasingly detailed. Apps can record your location, your level of exercise, the phone calls that you make and receive, the photographs that you take and who you share them with, and so on. Various studies have shown that this data provides a detailed and comprehensive insight into an individual’s habits and lifestyle, information that advertisers and marketers dearly love to have.

Indeed, this information can be surprisingly useful. The Google Now smartphone app uses information such as your location to provide details it thinks you might find useful, such as directions home or nearby restaurants.

But this service isn’t entirely altruistic. Google knows perfectly well that it can use this information to sell adverts and other services.

That raises an interesting question. If companies such as Google can create a business model based on the use of this kind of personal information, how much is this information worth? And how should we value it when it comes to deciding who should have access to it and who shouldn’t?

Today, we get an answer of sorts thanks to the work of Jacopo Staiano at the University of Trento in Italy along with a few pals. These guys have kitted out 60 people with smart phones that record all kinds of personal details and then created a kind of marketplace in which they could sell it. The idea was to find out how each person valued the information collected.

Unsurprisingly, people value certain kinds of information more highly than others. But exactly how they value it depends on a complex set of other factors, such as the conditions under which information was gathered.

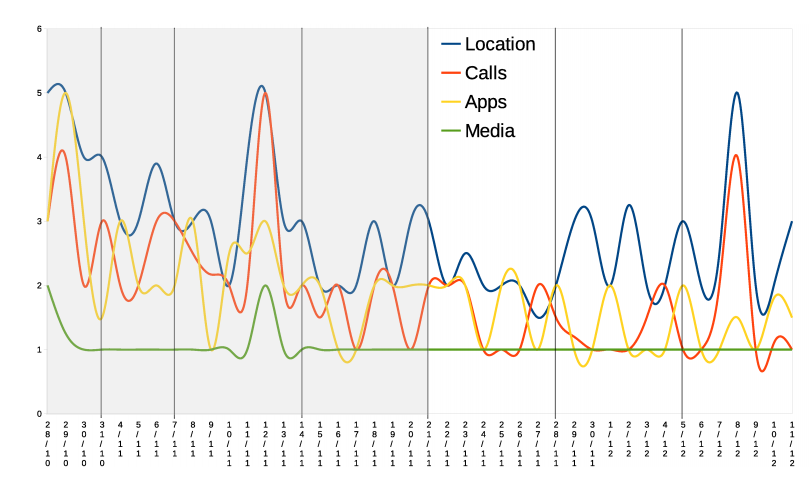

The experiment involved a kind of living lab in Italy that monitored people continuously. The team recruited 60 people to take part in the study and gave them each a smart phone that recorded phone calls made and received which applications were in use at any time and the time spent on them, the users’ locations throughout the day and the number of photographs taken.

Once a week, the participants took part in an auction to sell the raw data itself or the data after it had been processed. For example, they might sell a specific GPS location or the total distance traveled, or all of the locations visited on a specific day.

Staiano and co chose an unusual type of market called a reverse second-price auction strategy in which to sell this data. In this kind of auction, the winner is the person who sets the lowest price but he or she receives as payment the value of the second lowest price.

The money was paid out by the researchers who say this form of auction encourages participants to be honest about their valuations and has been used in similar information auctions in the past.

Halfway through the study, the team increased the frequency of the auctions from once a week to every day and found that this reduced the value of the bids as people found they could win more often.

In total, the team ran 596 auctions over 60 days and paid out a total of €262 in the form of Amazon vouchers to 29 participants. The median bid across all the data categories was €2. They also paid out €100 to one of the participants with the highest response rate who they chose using a raffle.

The results clearly show that some information is more highly valued than others. “We have found that location is the most valued category of personally identifiable information,” say Staiano and co. And participants tended to value processed information more highly as well because of their perception that it gave a greater insight into their lifestyle.

But interestingly personal information becomes even more highly valued in certain circumstances. For example, the study covered two unusual days. The first was a holiday in Italy known as the Immaculate Conception holiday. The second was a day of particularly high winds which caused multiple roadblocks and accidents.

“The median bids for all categories in these two days were significantly higher than for the rest of the days in the study,” say Staiano and co. In other words, participants value their information more highly on days that are unusual compared to typical days.

Another curious finding is that not all participants valued their personal data equally. In fact, people who travel more each day tend to value their personal information more highly.

Staiano and co also surveyed the participants on a regular basis asking them why they made their choices and also asking who they trusted most of their personal information. Unsurprisingly, they trusted themselves with this information more than they trusted organizations such as banks, telecommunications companies or insurance companies.

That’s an interesting insight into the way people assign a monetary value to their personal information. And it could have important implications for the future. It seems clear that the focus on protecting personal information is likely to become greater. But it also looks clear that some kind of market for personal data will emerge.

Just how that will happen is anybody’s guess. But one way or another, we are all going to have to think much more carefully about the value of our personal data, whether we are happy to sell it or not and if so, for how much.

No prizes for guessing which web giant is likely to be a pioneer of this kind of marketplace.

Ref: http://arxiv.org/abs/1407.0566 : Money Walks: A Human-Centric Study on the Economics of Personal Mobile Data

Note: This story has been updated to reflect that none of the researchers involved worked at Google at the time of the project.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.