GE Device Measures the Calories on Your Plate

Self-tracking devices like the Fitbit do a fair, if imperfect, job at measuring how much you move and then inferring how many calories you’ve burned in a day. But they don’t measure how many calories you consume. You can enter calorie estimates into an app, but doing so is a tedious and often inaccurate process.

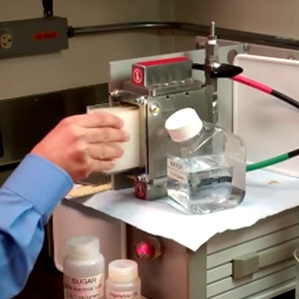

GE researchers have a prototype device that directly measures the calories in your food. So far it only works on blended foods—the prototype requires a homogenous mixture to get an accurate reading. But they’re developing a version of the device that will determine the calories in a plate of food—say, a burrito, some chips, and guacamole—and send the information to your smartphone.

Matt Webster, the senior scientist in diagnostic imaging and biomedical technologies at GE Research who invented the calorie counter, says eventually the device might be incorporated into a microwave oven or some other kitchen appliance. Heat your food, and at the same time get a readout of the precise calorie count, without measuring out portions and consulting nutritional charts.

Webster analyzed nutritional data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture—which contains detailed information on thousands of foods—and determined that it’s possible to get an accurate calorie estimate using just three pieces of data—fat content, water content, and weight. The calories from all the other constituents of food—such as sugar, fiber, and protein—can be approximated by subtracting the water and fat weight from the total weight.

In tests using the prototype to measure mixtures of oil, sugar, and water, results were within 5 to 10 percent of the results from standard, destructive means of measuring calorie content, such as the bomb calorimeter that measures food calorie content by burning it.

The device works by passing low-energy microwaves through a weighed portion of food and measuring how the microwaves are changed by the food—fat and water affect the microwaves in characteristic ways. Getting a reading is easy using existing equipment if the food is liquid or blended. Getting a good reading for a sandwich and chips will require “virtual blending” Webster says. That could be done by developing microwave antennas that form a more uniform distribution of microwaves than the current equipment and using algorithms to get an average, or by progressively scanning the food. In either case, the complete measurement could be taken in a second or two.

Others are developing devices that are being marketed as being able to count calories. For example, a pair of devices have emerged recently on crowd-funding sites. But those devices are limited to analyzing the surface of most foods (they work by measuring reflected light). This approach might work to recognize a piece of food as an apple, for example, whose caloric content can be looked up in a database. It wouldn’t easily work with a burrito, where most of the calories are wrapped up inside.

“We’re looking at waves that pass all the way through the food. So you’re getting a complete measurement of the entire food,” Webster says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.