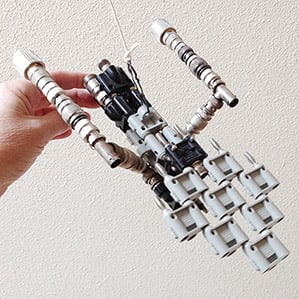

In her home office in Federal Way, Washington, Janet Freeman-Daily ’78 keeps a model of the starship Enterprise made out of spare parts from her days designing aerospace components. On difficult days—she’s one of 30 lung cancer patients in the world taking an experimental drug to treat a rare strain of the disease—it encourages her to remember everything she accomplished in her two decades as an aerospace engineer.

Freeman-Daily dubbed it the starship Connector-prise, an allusion to the electrical connectors used to put it together. “For years, while I worked on new products in aerospace, it hung in my office,” she says. “It was a gift from a dear friend in my MIT dorm who earned his Course 6 degrees before the digital age. Now that I’m retired and fighting cancer, I focus more on living in the moment and less on possessions. But this still occupies a place of honor. It’s a reminder of youth, friends, creativity, and hacking.”

Many such totems have occupied equal places of honor in the offices of MIT alumni across space and time. They range from ordinary objects to profoundly meaningful emblems of times past.

In his office at Maine Maritime Academy in Castine, Maine, Rick Armstrong ’65 describes a keepsake nearly 50 years old.

“I wouldn’t be here without my red square banner: ‘Tech Is Hell,’” he says. “Two years ago a friend happened to come by the office for the first time. Revelation: unbeknownst to either one of us, we were in the same class—me Course 13, he 10!”

Other totems are gifts from fellow alumni, offering inspiration to the recipients. Alexandre Oliveira ’10, a co-creator of the photo-book platform Storytree, sent classmate Bel Pesce ’10, a TED Fellow in Brazil, a “little box of dreams” after graduation. In it he painted the words “dream big” in Portuguese. “He painted the three different dreams I had at the time: moving back to Brazil, starting a company that touched many lives, and composing songs that would make people smile,” says Pesce, who has done all those things as an entrepreneur and musician.

Mark Krebs ’83, a brewer in Colorado, has a self-made honor affixed to his wall. “When I worked at Orbital Sciences, we had real difficulties with magnetic disturbances on our spacecraft,” Krebs recalls. “It was quite a trial, and I was proud of us all when we finally succeeded, so I made these certificates for everybody on the team. Referenced in the text is a mysterious metal whose name paid homage to a friendly scientist from NASA Goddard, Dr. Mario Acuña, who took us into his care and told of the many mysteries of the earth’s field.”

University of Michigan professor John Psarouthakis ’57 has offices in Michigan, Florida, and Edinburgh, Scotland, and he displays keepsakes in all of them: diplomas, honors, and, most dear to him, a photo of former MIT president Paul Gray ’54, SM ’55, ScD ’60, giving him a silver bowl for corporate leadership in 1988.

“I first met him back when I was volunteering on a visiting committee,” says Psarouthakis. “Paul asked me the most important thing I learned at MIT. I was reasonably well known then for my work on energy systems and heat transfer, so I said, ‘You’d probably think it was the second law of thermodynamics. But no, it was to not try solving a problem before I can define the problem fully.’ Too often, there’s a tendency to throw out solutions before you really articulate what the problem is.”

Also on Psarouthakis’s wall is an aerial photo of his native island of Crete; it was taken in space by Neil Armstrong and presented to him at a conference.

“I’ve always brought photos of my family with me to each office,” says Thomas Imrich ’69, SM ’71. He also displays aircraft models, mementos of the test flights he flew for Boeing and the FAA teams he led in his career. “On my desk right now I’m looking at my 747-8 model. I flew the last FAA certification on that plane,” he says.

Bob Macke ’96, a Jesuit priest working at the Vatican Observatory near Rome, is especially fond of an office totem that adds levity to his day. “A small figure of Dr. Doofenschmirtz from Phineas and Ferb sits atop the pycnometer that I built while I was at Boston College,” he says, referring to the evil scientist known for his wacky contraptions in a cartoon geared to young engineers. “A pycnometer is a device for measuring densities. It’s there because [as Doofenschmirtz would] I sometimes jokingly refer to the device as a ‘pycnominator.’”

Greg Burnett ’74 designs sets at Universal Studios Hollywood and has his share of movie memorabilia, including a minion from Despicable Me, magnets from Transformers, “and all the access badges from projects I’ve worked on.”

David Dobkin ’70 is dean of the faculty and professor of computer science at Princeton. But he’s also an amateur artist known for his collections, which were recently on view there. He keeps in his office towers of pennies that represent the statistical distribution of pennies minted in Philadelphia from 1975 to 1997.

Perhaps the most diverse office collection belongs to Terrafugia’s chief engineer, Andrew Heafitz ’91. On a crowded shelf are a “fossil fish that my parents gave me, a small meteorite that I bought when I went to see a rocket launch in Florida, a piece of coal that I found in my backyard, a piece of lava from a trip to Lanzarote, an arrowhead I found in Nevada, and a piece of petrified wood I found near a petrified forest.”

On a trip to Greece, Heafitz launched a camera affixed to a balloon over a remote archaeological site. The shape of the site in the resulting photo became the logo for one of his early startups, TacShot. Needless to say, the original photo still hangs in his office.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.