Digital Summit: Microsoft’s Quantum Search for the “Next Transistor”

Microsoft is making a significant investment in creating a practical version of the basic component needed to build a quantum computer, the company’s head of research said Monday.

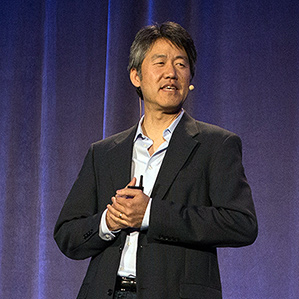

Speaking at MIT Technology Review’s Digital Summit event in San Francisco, Peter Lee likened the effort to research at Bell Labs in the 1940s that produced the silicon transistor, the basis of all computing today. “This is our attempt to find the analogous device to the transistor,” said Lee.

In an interview, he told MIT Technology Review that Microsoft had previously kept its quantum effort relatively quiet, but that positive results have convinced him to be more open. “One reason we’ve been a little cagey is that early on this was a fringe effort—now the physics community takes us seriously,” he said. “We are very serious about our quantum physics research and we’re expanding.”

Microsoft has a dedicated quantum computing research lab, known as Station Q, on the campus of University of California, Santa Barbara. It has also been supporting labs around the world with grants and donations of tools to aid research.

A quantum computer should be able to complete calculations that are effectively impossible for any conventional machine today. None has ever been built. Although the Canadian company D-Wave Systems has sold several machines it says are quantum computers, experts say there is still no definitive proof that they exploit quantum principles and can beat conventional machines (see “The CIA and Jeff Bezos Bet on Quantum Computing”).

Microsoft is not currently attempting to build a quantum computer. Rather, its research effort is aimed at developing a reliable version of the qubit, the key building block of a quantum computer.

Just like a transistor in a conventional computer, a qubit can switch between states that represent either a 1 or 0 of digital data. But a qubit can also exploit quantum effects to reach a “superposition state” that is both 1 and 0 at the same time. That would allow a quantum computer to process data many times faster than any conventional computer.

Researchers have built qubits of different designs and even used small numbers of them together for very basic calculations. But none are able to maintain a superposition state very reliably, making them impractical for anyone hoping to build a computer of any size. “We believe that current approaches will never scale,” said Lee.

Microsoft’s research focuses on a type of qubit known as a topological qubit that theory suggests would encode data in a much more robust way.

The theoretical basis of topological qubits was first sketched out at UC Santa Barbara roughly eight years ago, says Lee. Then, around four years ago, Microsoft researchers led work to pose a series of key tests that could show whether those ideas could work in reality. Microsoft funded several labs around the world to work on those questions, says Lee. “Two years ago the results started to come in positive.”

Work is now underway to actually build a working topological qubit. To support that effort, Microsoft has developed specialized tools for quantum experiments and given them to the academic community. Those tools range from cloud simulation platforms for theoretical work to new types of electronics for use in the super-cooled temperatures of quantum hardware experiments.

Meanwhile, Microsoft is already looking ahead to explore what could be done with a system of topological qubits once they are built. “Supposing that one day we have a quantum machine: would it be good for anything?” says Lee. “Today we have clear ideas in classical computing about problems we can solve but it’s very hard to conceive what’s possible with one of these theoretical machines.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.