Why the EPA Regulations Go Easy on Coal States

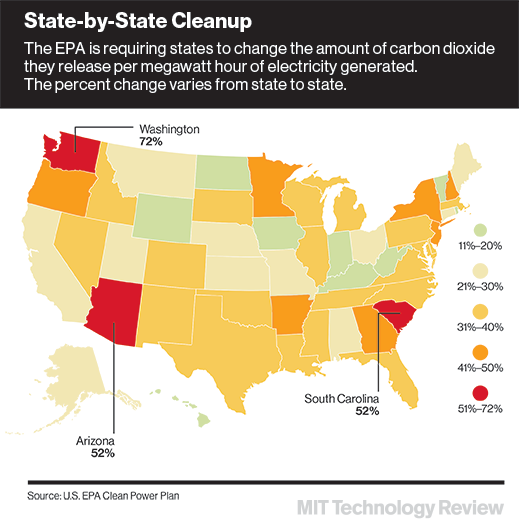

Last week the EPA released a plan to significantly reduce U.S. carbon dioxide emissions over the next 15 years (see “EPA to Take Biggest Step Ever to Fight Climate Change” and “EPA Issues Proposed Carbon Emissions Rules”). It turns out that some of the states faced with making the biggest changes to meet that goal aren’t the ones that rely heavily on the biggest source of emissions—coal power.

In some cases, states that have already planned big emissions reductions are making up for coal-heavy states such as Kentucky and Indiana.

Under the proposed regulations, the EPA set specific requirements for each state to account for regional differences that affect how hard it will be for various states to reduce their emissions. Some of those differences are practical or economic—wind power is more expensive in some places than others, and some states can draw on existing natural gas plants to reduce coal emissions.

But some of the differences are political, says David Victor, director of the Laboratory on International Law and Regulation at the University of California at San Diego. In some states, it’s hard to pass legislation requiring renewable energy, and the EPA took that into account, he says.

In the plan, the EPA says it “anticipates—and supports—states’ commitments to a wide range of policy preferences,” including decisions by some “to feature significant reliance on coal-based generation.”

Despite this attempt to mollify coal states, politicians from some of these states still object to the proposed regulations. Mitch McConnell, the Republican senator from Kentucky, complains that the proposed regulations help states such as New York while hurting his own—even though the EPA plan requires New York to cut its carbon dioxide emissions (per megawatt-hour of electricity produced) by 44 percent, while Kentucky needs to cut its rate of emissions by only 18 percent.

In many cases, the EPA based its decisions on plans the states already have in place. Based on Colorado’s existing renewable energy plan, for example, the EPA expects it could get 20 percent of its power from renewable energy by 2030, and requires the state to reduce its rate of emissions by 36 percent. In contrast, the EPA expects that Kentucky will get only 2 percent of its power from renewable energy.

Washington is being asked to cut its rate of emissions by 72 percent, the highest requirement for any state. But that’s because it already plans to close its only coal-fired power plant, which accounts for a large share of its emissions (the state gets most of its electricity from hydroelectric plants).

The EPA’s goals were also influenced by the practicality of a given technology. Retrofitting power plants so they can capture carbon dioxide, for example, was considered too expensive and impractical in many cases. If carbon capture were cheaper, states with large amounts of coal and little renewable energy or natural gas power would have an easier time of reducing their emissions.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.