Stem-Cell Treatment for Blindness Moving Through Patient Testing

A new treatment for macular degeneration is close to the next stage of human testing—a noteworthy event not just for the millions of patients it could help, but for its potential to become the first therapy based on embryonic stem cells.

This year, the Boston-area company Advanced Cell Technology plans to move its stem-cell treatment for two forms of vision loss into advanced human trials. The company has already reported that the treatment is safe (see “Eye Study Is a Small but Crucial Advance for Stem-Cell Therapy”), although a full report of the results from the early, safety-focused testing has yet to be published. The planned trials will test whether it is effective. The treatment will be tested both on patients with Stargardt’s disease (an inherited form of progressive vision loss that can affect children) and on those with age-related macular degeneration, the leading cause of vision loss among people 65 and older.

The treatment is based on retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells that have been grown from embryonic stem cells. A surgeon injects 150 microliters of RPE cells—roughly the amount of liquid in three raindrops—under a patient’s retina, which is temporarily detached for the procedure. RPE cells support the retina’s photoreceptors, which are the cells that detect incoming light and pass the information on to the brain.

Although complete data from the trials of ACT’s treatments have yet to be published, the company has reported impressive results with one patient, who recovered vision after being deemed legally blind. Now the company plans to publish the data from two clinical trials taking place in the U.S. and the E.U. in a peer-reviewed academic journal. Each of these early-stage trials includes 12 patients affected by either macular degeneration or Stargardt’s disease.

The more advanced trials will have dozens of participants, says ACT’s head of clinical development, Eddy Anglade. If proved safe and effective, the cellular therapy could preserve the vision of millions affected by age-related macular degeneration. By 2020, as the population ages, nearly 200 million people worldwide will have the disease, estimate researchers. Currently, there are no treatments available for the most common form, dry age-related macular degeneration.

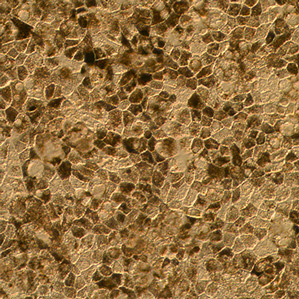

ACT’s experimental treatment has its origins in a chance discovery that Irina Klimanskaya, the company’s director of stem-cell biology, made while working with embryonic stem cells at Harvard University. These cells have the power to develop into any cell type, and in culture they often change on their own. A neuron here, a fat cell there—individual cells in a dish tend to take random walks down various developmental paths. By supplying the cultures with fresh nutrients but otherwise leaving them to their own devices for several weeks, Klimanskaya discovered that the stem cells often developed into darkly pigmented cells that grew in a cobblestone-like pattern. She suspected that they were developing into RPE cells, and molecular tests backed her up.

Now that her discovery has advanced into an experimental treatment, Klimanskaya says she is excited by the hints that it may be able to preserve, and perhaps restore, sight. She recalls a voice mail she received during her second year at ACT: a person blinded by an inherited condition thanked her for her work, whether or not there was a treatment available for him. “When you get a message like this, you feel like you are not doing it in vain,” she says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.