The Data Mining Techniques That Reveal Our Planet’s Cultural Links and Boundaries

The habits and behaviors that define a culture are complex and fascinating. But measuring them is a difficult task. What’s more, understanding the way cultures change from one part of the world to another is a task laden with challenges.

The gold standard in this area of science is known as the World Values Survey, a global network of social scientists studying values and their impact on social and political life. Between 1981 and 2008, this survey conducted over 250,000 interviews in 87 societies. That’s a significant amount of data and the work has continued since then. This work is hugely valuable but it is also challenging, time-consuming and expensive.

Today, Thiago Silva at the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais in Brazil and a few buddies reveal another way to collect data that could revolutionize the study of global culture. These guys study cultural differences around the world using data generated by check-ins on the location-based social network, Foursquare.

That allows these researchers to gather huge amounts of data, cheaply and easily in a short period of time. “Our one-week dataset has a population of users of the same order of magnitude of the number of interviews performed in [the World Values Survey] in almost three decades,” they say.

Food and drink are fundamental aspects of society and so the behaviors and habits associated with them are important indicators. The basic question that Silva and co attempt to answer is: what are your eating and drinking habits? And how do these differ from a typical individual in another part of the world such as Japan, Malaysia, or Brazil?

Foursquare is ideally set up to explore this question. Users “check in” by indicating when they have reached a particular location that might be related to eating and drinking but also to other activities such as entertainment, sport and so on.

Silva and co are only interested in the food and drink preferences of individuals and, in particular, on the way these preferences change according to time of day and geographical location.

So their basic approach is to compare a large number individual preferences from different parts of the world and see how closely they match or how they differ.

Because Foursquare does not share its data, Silva and co downloaded almost five million tweets containing Foursquare check-ins, URLs pointing to the Foursquare website containing information about each venue. They discarded check-ins that were unrelated to food or drink.

That left them with some 280,000 check-ins related to drink from 160,000 individuals; over 400,000 check-ins related to fast food from 230,000 people; and some 400,000 check-ins relating to ordinary restaurant food or what Silva and co call slow food.

They then divide each of these classes into subcategories. For example, the drink class has 21 subcategories such as brewery, karaoke bar, pub, and so on. The slow food class has 53 subcategories such as Chinese restaurant, Steakhouse, Greek restaurant, and so on.

Each check-in gives the time and geographical location which allows the team to compare behaviors from all over the world. They compare, for example, eating and drinking times in different countries both during the week and at the weekend. They compare the choices of restaurants, fast food habits and drinking habits by continent and country. The even compare eating and drinking habits in New York, London, and Tokyo.

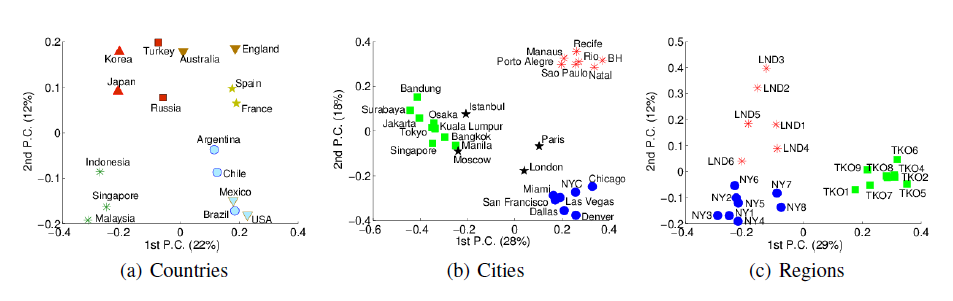

The results are a fascinating insight into humanity’s differing habits. Many places have similar behaviors, Malaysia and Singapore or Argentina and Chile, for example, which is just as expected given the similarities between these places.

But other resemblances are more unexpected. A comparison of drinking habits show greater similarity between Brazil and France, separated by the Atlantic Ocean, than they do between France and England, separated only by the English Channel.

And the differences in temporal habits are interesting too. For example, Brazilians tend to eat and drink later than Americans or the English. And while the number of check-ins at drinking establishments in the US and Brazil peak late into the evening at weekends, the English start at lunchtime and appear to drink throughout the day.

Cities within a country also seem to show very similar behavior. For example, most U.S. cities exhibit a weekday pattern similar to New York and Chicago with three distinct peaks around breakfast, lunch and happy hour (around 6 p.m.). “However, Las Vegas is one exception, since there is an intense activity during the dawn, besides many other peaks of activities that do not occur in other cities,” they say.

The data also shows cultural boundaries around the world and even inside cities themselves.

Finally, Silva and co compare their data to the cultural map produced by the World Values Survey. While this team has studied only habits related to food and drink, the survey studies many different aspects of cross-cultural variation.

Nevertheless the comparison is eye-opening. Even though the Foursquare data only applies to one aspect of human culture, the results from both approaches shows all kinds of resemblances. “The similarities are striking,” say Silva and co.

They point out only two major differences. The first is that no Islamic cluster appears in the Foursquare data. Countries such as Turkey are similar to Russia, while Indonesia seems related to Malaysia and Singapore.

The second is that the U.S. and Mexico make up their own individual cluster in the Foursquare data whereas the World Values Survey has them in the “English-speaking” and “Latin American” clusters accordingly.

That’s exciting data mining work that has the potential to revolutionize the way sociologists and anthropologists study human culture around the world. Expect to hear more about it

Ref: http://arxiv.org/abs/1404.1009: You Are What You Eat (and Drink): Identifying Cultural Boundaries By Analyzing Food & Drink Habits In Foursquare

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.