Cities, Networks, and the Counterintuitive Nature of Suicide

Cities provide huge benefits for those who live in them and these are easy to see when you compare cities of different sizes. As cities get bigger, the number of jobs, houses, and water consumption all scale with the size of the population.

But income, productivity, and bank deposits scale even faster, at a rate greater than the increase in population size, or super linearly. People in big cities clearly benefit from an economy of scale that also improves their quality of life. And the bigger a city is, the greater the benefit.

But there are also negative qualities that scale super-linearly with city size: living costs and pollution, for example.

Little is known about the impact these negative factors have on the locals. So an important question is whether they change human behavior in negative ways.

Today we get an answer thanks to the work of Hygor Piaget Melo at the Federal University of Ceará in Brazil and a couple of pals. These guys have measured the way that the rate of homicides, suicides, and traffic accidents scale with city size.

It’s easy to imagine that these kinds of indicators go hand in hand with the negative urban indicators of high living costs and greater pollution. But Melo and co say the link isn’t as straightforward as might be imagined and their results throw up a considerable surprise.

The study of how things scale is known as allometry. Perhaps the most famous example is Kleiber’s law which states that the metabolic rate of all animals scales with their mass to the ¾ power. Biologists have long known that this relation holds true over an extraordinary 27 orders of magnitude, from bacteria to blue whales.

But in recent years, anthropologists have discovered that similar allometric laws describe various properties of cities. Wages scale super linearly with city size—which is presumably one reason why so many people are attracted to cities. Jobs scale at the same rate. By contrast, certain characteristics such as the number of gas stations scale sub-linearly.

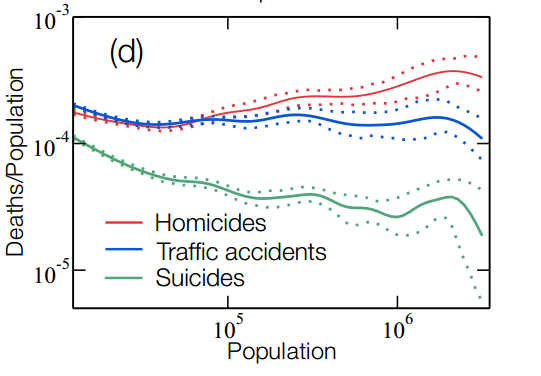

But Melo and co’s real interest is in the rate of scaling for homicides, suicides, and fatal traffic accidents. So they gathered data on the number of suicides, homicides, and deaths from traffic accidents for all cities in Brazil and for each county in the U.S. They then plotted this against the population size.

The results are not quite what you might imagine. It turns out that homicides scale super-linearly. So big cities have more murders per head than smaller ones.

By contrast, deaths from traffic accidents scale isometrically. In other words, the number of deaths per head is the same for all cities, whatever their size.

But the real surprise is the rate of suicides, which scale sub linearly. In other words, bigger cities have fewer suicides per capita than smaller ones.

That prompts an interesting question. If population size is a factor in the rate of suicides, what is the nature of the cause and effect?

Melo and co suggest that the kind of emotional intensity associated with suicide might dissipate more easily in big cities, where there are more people to shoulder the burden, an idea known as emotional epidemy.

“This phenomenon can explain the systematic attenuation through the social network of contagious emotions states of potentially suicidal individuals,” they say. Put another way, suicides are essentially a social phenomenon.

That’s not the first evidence pointing in this direction. Epidemiologists have long noticed that suicide rates drop during periods of war, perhaps because of the same phenomenon—that people pull together in times of difficulty, an activity that reduces suicidal tendencies.

If that’s the case, then big cities and war zones have more in common than you might immediately be apparent.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1402.2510 : Statistical Signs of Social Influence on Suicides

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.