For Mice, and Maybe Men, Pain Is Gone in a Flash

Some of the mice squeaked in pain when researchers aimed a blue light at their paws. Other mice felt nothing at all when zapped with heat.

In the latest demonstration of optogenetics, a versatile but complex technology for controlling nerve cells, a research team at Stanford University has sketched out how patients afflicted by chronic pain might one day find relief: simply by pressing a bright flashlight to their skin.

“Patients could be given their own ability to create a pain block on demand,” says Michael Kaplitt, a neurosurgeon and chief scientific officer of Circuit Therapeutics, a three-year-old Palo Alto, California, biotechnology startup now working on a pain treatment along with some of the Stanford scientists.

Optogenetics is a breakthrough technology that is giving scientists precise control over what animals feel, how they behave, and even what they think. It relies on modifying the DNA of neurons so that they send signals—or are blocked from firing—in response to light (see “Brain Control”). The technique was invented nine years ago, partly in the laboratory of Karl Deisseroth, one of Circuit’s cofounders and an author of the new pain study.

So far, the most striking use of optogenetics has been to produce effects directly inside animals’ brains, using light piped in with an implanted fiber-optic cable. In an earlier study, Deisseroth’s group made mice feel fear or become fearless (“An On-Off Switch for Anxiety”).

Circuit, which now has 47 employees, is working to engineer light sources and perfect genetic tools to take advantage of optogenetics. Kaplitt says that in addition to its research on pain, the company hopes to figure out how to treat serious psychiatric disease with implants that carry light into the brain.

But controlling nerves outside the brain could prove easier. The sensitive nerve endings, or nociceptors, that fire off warnings in response to heat or pressure lie only two hair-breadths beneath human skin, and could be controlled by a bright handheld light. “We have engineers thinking about what that kind of device would look like,” says Kaplitt. “Pain is a perception. So the idea is to stop the perception of it.”

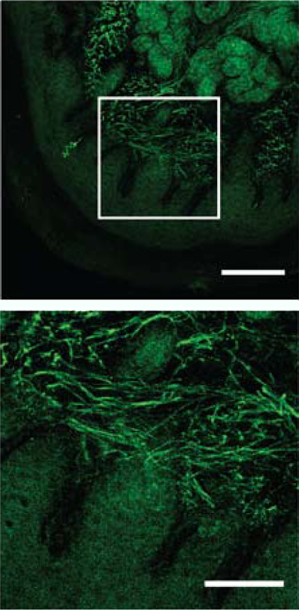

In the Stanford group’s latest work, published in the journal Nature Biotechnology, they first used gene therapy to install light-sensitive molecules into the nerve endings in the skin of mice. Each animal was then placed into a small plexiglass chamber with a transparent floor.

When the researchers shined blue light through the floor, the mice “flinched,” cried out, or “engaged in prolonged paw licking,” all signs of pain. The team could also block sensation. In those tests, mice that were bathed in yellow light designed to block nerve impulses weren’t greatly bothered by a band pinching their leg. When the researchers pointed hot infra-red beams at their paws, they were slow to react.

The work builds on earlier experiments at both Stanford and by researchers at McGill University. “The reason this paper is exciting is that it raises two prospects. One is that you can essentially turn on and off nerves causing pain at will. The other is that they illuminated the animal from the outside and still got the effect,” says Kaplitt.

Pain is the main reason people seek out doctors, running up $635 billion a year in health spending in the U.S. Right now, doctors can’t do much, and pain pills can have unfortunate effects, sometimes leaving users with foggy minds or hard-to-beat addictions.

There are plenty of obstacles ahead for an optogenetics treatment. It might prove difficult to reach the right nerve cells with light. And it relies on gene modification, itself an experimental technology. A decade or more of experiments and studies lie ahead before any treatment is available.

Circuit has raised funds from investors including Stanford as well as former Google executives David Jeske and Scott Hassan. But it isn’t the only company developing a pain product. MIT researcher Ed Boyden, who co-invented optogenetics at Stanford, has founded a competing firm, Eos Neuroscience. That company also is working on ways to use optogenetics to treat pain, CEO Ben Matteo says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.