Social Media Analysis Reveals The Complexities Of Syrian Conflict

Social media has become a fundamental tool of social change all over the world. Nowhere is this more evident than the middle east. Platforms such as Twitter and Youtube played a major role in the Arab Spring, the civil uprisings in 2010 that spread from Tunisia to Egypt to Libya to Yemen and beyond.

But the event most heavily covered by social media is the civil war in Syria, which has now raged for almost three year. The conflict has been extensively recorded on videos which are regularly uploaded to YouTube and then tweeted around the world. All sides in the conflict seem to be engaged with numerous social media accounts.

So an interesting question is to what extent does social media activity reflect the situation on the ground. That’s exactly the problem addressed today by Derek O’Callaghan at University College Dublin and a few pals. Their conclusion is that “social media activity in Syria is considerably more convoluted than reported in many other studies of online political activism that find a straightforward polarization effect.”

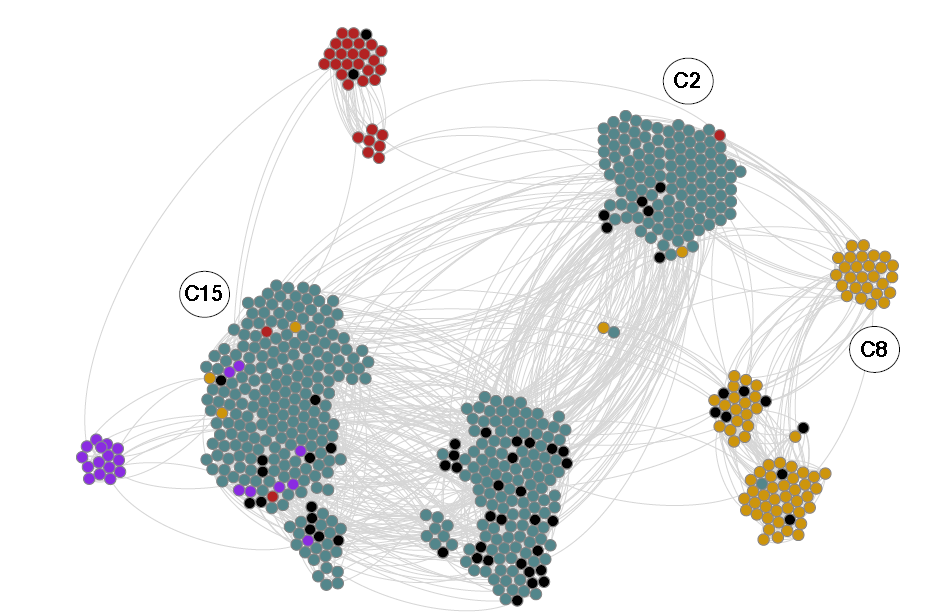

These guys studied over 600 Twitter and YouTube accounts that post or link to content related to the Syrian conflict. Since many of these accounts point to each other or similar content, they form communities amongst themselves. So O’Callaghan and co used a standard community detection algorithm to tease apart how the accounts were aligned.

The results reveal 16 separate communities which together form four clearly aligned groups. The first are Jihadist, made up of three communities and including accounts associated with Al-Qa’ida.

The second are Kurdish, consisting of a community of political parties and another of youth organisations.

The third is Pro-Assad and consists of essentially one community of supporters of the current Syrian regime.

The final group is made up of ten communities who are characterised as secular or moderate opposition. This includes accounts that support the Free Syrian Army and the Syrian National Coalition.

O’Callaghan and co go on to analyse a representative community from each group. For example, one community supporting the Free Syrian Army consists of 105 social media accounts including one with 73,000 followers that supplies photographs of unidentified bodies so that people can help identify them.

By contrast, one of the Jihadist communities carries very different content. “Photos tweeted by these accounts include many of weaponry and attacks, also close-ups of ‘martyred’ fighters and a small number of individuals holding up severed human heads,” report O’Callaghan and co.

The moderate/secular community these guys focus on is largest of all with 137 accounts. In contrast to the other groups, a significant proportion of tweets are in English, reflecting the fact that these accounts are often run by the Syrian diaspora in other countries. Female users are also more prominent in this community/

One interesting observation is the difference in the way these communities react to events on the ground. In particular, O’Callaghan and co study the Ghouta chemical weapons attack on 21 August 2013. They point out that while the moderate/secular community reacted immediately by posting videos of the attack on you Tube, the Jihadist community took two days to respond.

And the volume of response was different too. The moderate/secular community uploaded 440 videos on the day of the attack and even more in the days that followed. By contrast, the Jihadist committee uploaded only 37 videos two days after the attack and fewer than this in the days of followed.

O’Callaghan and co do not draw any conclusions from this but it must surely reflect some aspect of the engagement on the ground.

What’s interesting here is that other studies of the relationship between social media and political activities clearly shows a polarising effect in which people divide into two broadly opposing communities. But the situation in Syria is significantly more complex.

The implications of this for a future peace settlement are far from clear. But O’Callaghan and co have plans to continue monitoring Syrian online activity and how the structure of the groups they have found varies over time. Perhaps that will offer some insight into how this increasingly bitter conflict might pan out.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1401.7535: Online Social Media in the Syria Conflict: Encompassing the Extremes and the In-Betweens

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.