Coming Soon: Smart Glasses That Look Like Regular Spectacles

For all the hype around smart glasses, none of them actually look like normal glasses. But Vuzix, which develops wearable display technology for military and industrial applications, plans to change that this summer by releasing a pair of sleek wraparound shades that will let users see colorful images projected over objects in the real world.

Vuzix CEO Paul Travers says his company’s sunglasses will not only be less bulky and obtrusive than Google Glass, they’ll also provide an augmented reality experience that actually resembles the one portrayed in Google’s first promotional video for Glass, in which useful bits of information like navigational cues are displayed in the middle of the wearer’s field of vision. This isn’t possible today with Glass, whose display sits off to the side, above the right eye, and is the visual equivalent of a 25-inch high-definition television seen from eight feet away.

Everyone trying to make glasses with computers in them faces similar problems, Travers says: “Look and feel is one of them. Another is user interface.” Vuzix’s technology is meant to address both challenges by taking advantage of relatively recent advances in the ability to control the movement of light at the nanoscale.

With conventional optics, projecting images into the middle of someone’s field of vision would call for a much thicker lens than the one in Glass, says Travers. But the lenses in Vuzix’s spectacles will be less than two millimeters thick. That’s possible because the company employs a “waveguide” technology that acts like a fiber optic cable, directing light from tiny displays housed in the temples of the glasses toward the lenses. There the light gets scattered by nanoscale structures in the lenses called gratings; variations in how the light is sent to the gratings can be used to produce colorful high-resolution images.

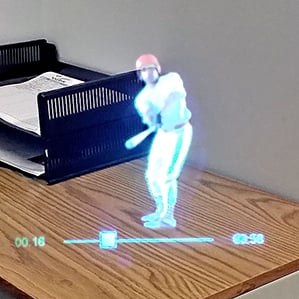

Vuzix first used this technology in a recently released monocle meant for industrial applications such as displaying technical information about a piece of equipment that a worker is repairing. It sells for nearly $6,000, but the sunglasses, says Travers, will have a “consumer price point.” A consumer product might display location and mapping data, or allow for augmented reality gaming.

Vuzix developed the technology through a partnership with Nokia, which began pursuing wearable displays several years ago. Nokia has since sold the equipment needed to manufacture such displays to Vuzix.

Whether or not Vuzix’s glasses catch on, it’s already clear that other companies will be racing to produce alternatives to Google’s product. At this week’s International Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Epson launched its own augmented reality glasses. The product doesn’t use the nanoimprint lithography technology that Vuzix uses to etch tiny gratings on the lenses; instead it makes use of more traditional optics technology. It looks more like regular glasses than Glass does, but it’s still rather bulky and conspicuous.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.