Self-Driving Car Tech Could Help Make Solar Powered EVs Practical

Putting solar panels on an electric car so that you don’t have to plug it in to charge it might sound like a good idea. But the amount of sunlight that hits the surface of a car isn’t enough to completely charge its battery in a day, even if the car is left out in the sun all day, and even if solar panels were far more efficient than they are now. Toyota offers solar panels on its Prius, but they only generate enough power to run a ventilation fan.

At the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Ford is showing off an idea for how to get more power out of the solar panels, enough to completely charge the battery in its C-Max plug-in hybrid in 6 hours, providing 21 miles of range. That’s enough to cover the commute of about half of the people in the country. Technology used for automated parking is part of what makes it possible.

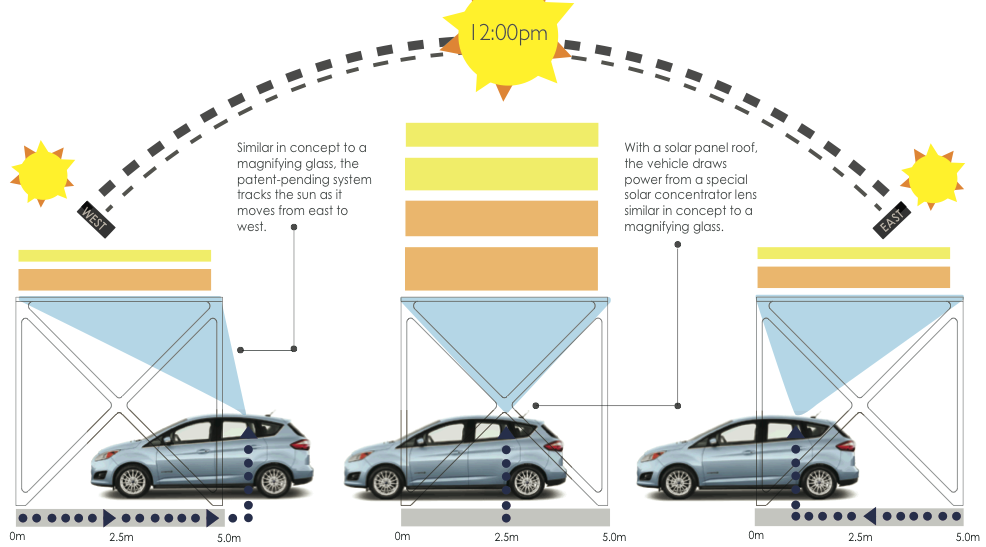

Instead of using only the sunlight that falls on the car, Ford suggests building tall carports whose roofs are made of a type of flat lens, called a Fresnel lens. These will gather sunlight over an area about 10 times larger than the surface of a car and focus it on solar panels on the roof of the car, greatly increasing the amount of solar energy those panels can generate.

The idea of concentrating sunlight to generate power is an old one. What’s new is Ford’s strategy for keeping down the cost of the system. As the sun moves across the sky, the point where the lens focuses the light moves. In conventional concentrating systems, the lens is mounted on a costly tracking system so that it can follow the sun throughout the day, keeping sunlight focused on the solar panels. Instead of moving the lens, Ford moves the car.

The car’s software keeps track of the path of the sun on any given day of the year to help determine how the car should move. It also monitors the amount of sunlight the solar panels are generating to make sure the car has moved to the right place.

Why not just put solar panels on the carport and use those to charge the car? In theory at least, Ford’s proposed system could be cheaper. The lens can be made of plastic and be cheaper than the dozens of solar panels you’d need to generate the same amount of power.

So far, the system is just a concept—Ford doesn’t have plans to sell them anytime soon. It has to work out, among other things, how to keep people and objects out of the the path of the concentrated sunlight when the car isn’t there (the beam could burn you).

The system isn’t exactly the ideal of the solar-powered car—which would be to allow you to keep your car charged wherever you go, giving you freedom like you have in a conventional car that can be refueled at ubiquitous gas stations. It’s hard to imagine Ford’s carports installed everywhere (they’re 5 meters tall and bigger than an ordinary carport), and they charge too slowly for road trips. They might be useful at workplaces, but providing outlets for plugging in would probably be cheaper, and it would work with electric cars that don’t have solar panels.

Tesla Motors has another approach to solar powered cars that might work better. It plans to use solar panels to charge batteries stored at its supercharging stations. Those batteries could then quickly charge electric cars, and get them back on the road. Such systems are expensive, but could still produce electricity cheaply enough to compete with powering a conventional car with gasoline, especially as the price of solar panels and batteries continues to fall.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.