Wikipedia’s Secret Multilingual Workforce

Wikipedia aims to provide free online access to all human knowledge. And a cursory look at its vital statistics appear to indicate that it’s well on its way to achieving that. The organisation has 77,000 active contributors working on over 22 million articles in 285 languages. All this attracts some 500 million unique visitors a month.

And yet a look beyond these figures reveals a subtle but important problem: there is surprisingly little overlap between the content in different language editions. No one edition contains all the information found in other language editions. And the largest language edition, English, contains only 51 per cent of the articles in the second largest edition, German.

This problem is known as self-focus bias and it places a significant limit on the access to knowledge that Wikipedia provides. It means that Wikipedia not only offers people access to a mere fraction of human knowledge but to a mere fraction of its own articles.

There are a group of people who could change this, says Scott Hale at the University of Oxford in the UK. He believes that people who edit Wikipedia in more than one language are the key. “Such multilingual users may serve an important function in diffusing information across different language editions of the project,” he says.

But do they actually play this role? Today, Hale reveals the results of his study of multilingual editors of Wikipedia. He says they turn out to be a small but important minority of editors who play a crucial role in helping to reduce the level of self-focus bias in each edition.

Hale began by crawling the edits to Wikipedia between 8 July and 9 August this year, which are broadcast in near real-time over Internet Relay Chat. He excluded minor edits and those made by bots and unregistered users. That left 3.5 million significant edits by 55,000 editors.

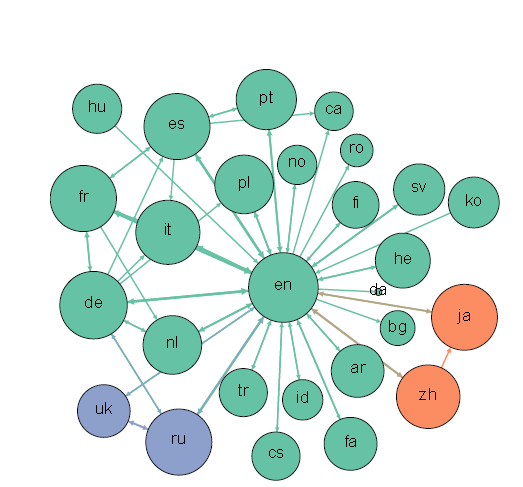

Hale then looked for editors who were active in more than one language edition and found more than 8,000 of them or about 15 per cent of the total. It was these multilingual editors that he studied further.

It turns out that some editions have more multilingual editors than others and in general smaller editions have a higher percentage of multilingual editors. The most significant outliers with the highest proportion of multilinguals were Esperanto and Malay while Japan had significantly fewer multilingual editors than its size would suggest.

Significantly, these multilingual editors are more active than their monolingual counterparts making, on average, 2.3 times as many edits.

What’s more, almost half of the articles added by multilingual editors are not edited at all by monolingual editors. Multilinguals also tend to edit the same articles in different languages. That’s significant because it implies that they are transferring new articles from one edition to another.

“This suggests that multilingual users are making unique contributions not duplicated by monolingual users and that in many cases multilingual users are working on the same article in multiple languages,” says Hale.

That’s interesting work. “Overall, this study shows multilingual users play a unique role on Wikipedia editing articles different to those edited by monolingual users,” concludes Hale.

And that’s an important job. If Wikipedia is to tackle the problem of self-focusing bias, it will need more editors like them. But just where they will come from is another question altogether.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1312.0976: Multilinguals and Wikipedia Editing

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.