Physicists Discover World’s First Naturally Occurring Topological Insulator

Topological insulators are one of the more exciting new materials in science. This stuff is odd because is a conductor on the surface but an insulator inside, rather like a block of ice in which melting water flows around the outside but is trapped as a solid in the middle.

But topological insulators have another property. The electrons flowing over the surface of a topological insulator are all aligned in a specific way. In fact, their “spins” are locked at right angles to their direction of motion.

This spin-momentum locking means that the electrons are immune from the buffeting they would get inside an ordinary conductor. Instead, the electrons can move through perfect topological insulators with 100 percent efficiency, even at room temperature.

That unique behaviour has excited physicists and electronics engineers alike. It means that topological insulators could form the basis of an entirely new generation of electronic devices that encode information using both the spin and the charge of an electron.

But there’s a problem. Topological insulators are few and far between. Physicists predicted their existence in solids in 2005 and synthesised the first example in 2008—a complex crystalline structure based on bismuth antimonide. But the difficulty in making other examples is a serious problem for the emerging technology of spintronics.

That looks set to change. Today, Pascal Gehring at the Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research in Stuttgart and a few pals have found the first example of a naturally occurring topological insulator in a sample of quartz from a mine in the Czech Republic. The discovery raises the prospect that other naturally occurring materials may be topological insulators too.

The new material is a grey, metallic mineral called Kawazulite which is made of bismuth, tellurium, selenium, and sulphur. The name comes from the Kawazu mine in Japan, where it was first discovered.

Given kawazulite’s crystal structure, materials scientists have suspected that it might act as a topological insulator. Indeed, they have synthesized the stuff in the lab and measured its properties to find out.

In every case, however, the predicted topological insulation failed to materialise because of defects in the synthesized material’s structure.

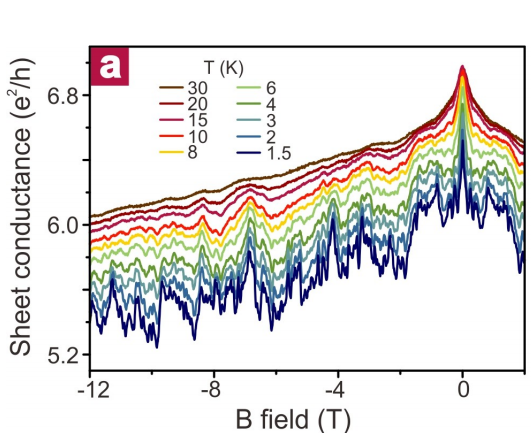

Now Gehring and co have created single crystalline sheets of the mineral by cleaving them from a naturally occurring crystal. When they measured the properties of this sheet, it turned out to be a conductor on the surface and an insulator inside, just as predicted.

The team speculate that naturally occurring kawazulite has fewer defects than its synthetic cousin because it is so old: any defects have dropped out of the structure during the millions of years since it formed.

The question now is whether it is possible to make enough single-crystal sheets from naturally occurring kawazulite to enable this stuff to be put through its paces by physicists working on the next generation of spintronic devices.

If they can perfect these devices, the electronics industry could one day come to rely on naturally occurring topological insulators from quartz mines in Japan and beyond.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1311.6637 : A Natural Topological Insulator

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.