Monkeys Drive Two Virtual Arms with Their Thoughts

How much dexterity can neurotechnology give to patients who are paralyzed? A study in monkeys suggests tasks that depend on the movement of two arms are within reach.

In the last year, researchers have reported amazing capabilities in patients to perform real-world tasks using a robotic arm. The patients control the arm with the help of brain implants that record their movement intentions. One patient was able to give herself a drink of coffee despite being paralyzed for 15 years (see “Brain Chip Helps Quadriplegics Move Robotic Arms”). Another patient who is completely paralyzed below the neck was able to feed herself a bit of chocolate (see “Patient Shows New Dexterity with a Mind-Controlled Robot Arm”).

Now, in a monkey study reported in Science Translational Medicine on Wednesday, researchers suggest that in the future, patients may be able to use brain-machine interfaces to control two arms.

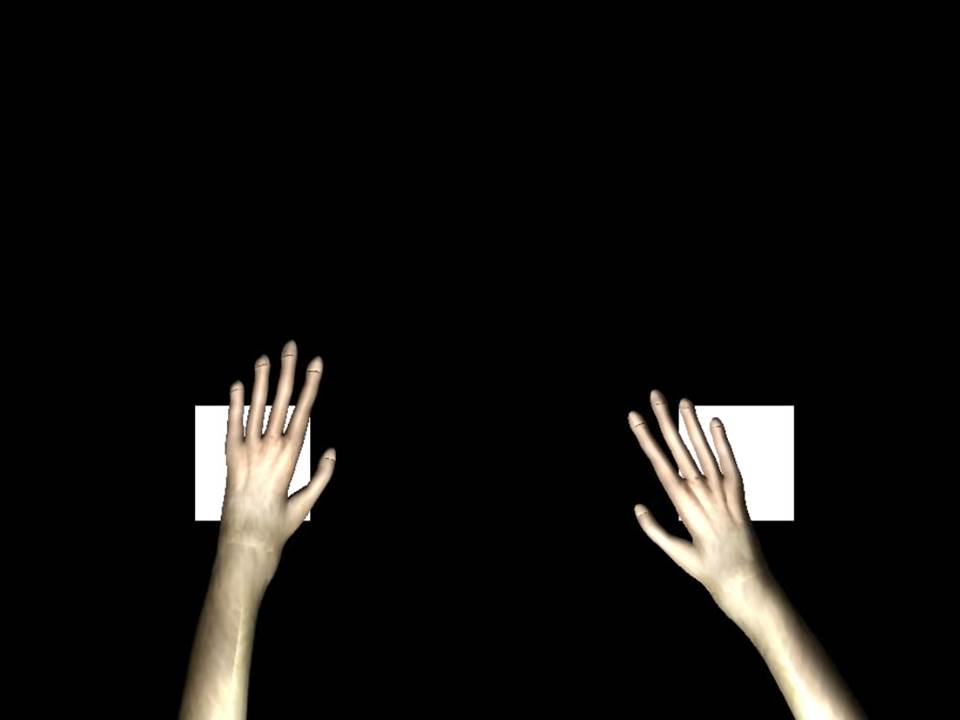

Duke University Medical Center neuroscientist Miguel Nicolelis and team implanted microeletrode arrays into several areas of the brains of two monkeys. At a given time, the arrays were able to record from around 500 neurons in each monkey, the greatest number of neurons reported yet. Through these implants, the monkeys were able to control virtual arms on a black screen to touch white circles or squares (see above) in tasks that were rewarded with juice treats.

While the monkeys were moving two hands, the researchers saw distinct patterns of neuronal activity that differed from the activity seen when a monkey moved each hand separately. Through such research on brain –machine interfaces, scientists may not only develop important medical devices for people with movement disorders, but they may also learn about the complex neural circuits that control behavior. Understanding whole-neural-circuit activity is a major goal of the U.S. government’s BRAIN initiative (see “Why Obama’s Brain-Mapping Project Matters”).

“Simply summing up the neuronal activity correlated to movements of the right and left arms did not allow us to predict what the same individual neurons or neuronal population would do when both arms were engaged together in a bimanual task,” said Nicolelis in a released statement. “This finding points to an emergent brain property – a non-linear summation – for when both hands are engaged at once.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.