First 3D Movies From a Single Pixel Camera

Single pixel cameras are taking the world of imaging by storm. These counterintuitive devices have the ability to photograph an entire scene in 3D and at a resolution of choice using a single pixel. Some versions do not even need a lens. These resultant images are entirely free of the optical aberrations that lenses can introduce; indeed the entire scene is always in focus.

Today, Gregory Howland at the University of Rochester in New York State and a few pals take this new technique even further. These guys have built a single pixel camera capable of making 3D images, used it to create a video images and even to track a moving object for the first time.

Single pixel cameras rely on a technique known as compressed sensing. The idea is to pass the light from a scene through a medium that randomises it and then focuses it on to a single pixel. This randomising medium could be a piece of frosted glass, a spatial light modulator or, as in this case, a digital micro-mirror device in which the mirrors are arranged at random.

It’s easy to imagine that the light reaching the pixel contains no information about the original scene. That isn’t the case.

To see why, imagine repeating this process many times, each with the micro-mirrors arranged in another random pattern. The signals picked up by the single pixel may seem random but in fact they are correlated because they all come from the same source–the original scene.

So the trick behind compressed sensing is to analyse the data in a way that finds this correlation. Once the correlation is known, it is relatively straightforward to reconstruct the original scene.

That produces a simple 2D image with a resolution that depends on the number of single pixel samples that have been taken.

Making 3D image is straightforward too. For this, the scene must be illuminated by a laser light and the single-pixel circuitry gated so that it is sensitive for a short instant after the illumination, when the light bounces back.

In this way, it is possible to sample light that returns from a specific distance from the camera. And by changing the timing of the gating, it is possible to build up an entire 3D image.

That’s essentially what Howland and co have done. But they’ve gone further than previous single pixel cameras by producing a video of a moving object.

One limitation of this technique is that it can take minutes or even hours to build up enough single pixel samples to create a high resolution image. Howland and co have speeded things up with a digital micro-mirror that can display some 1400 different random patterns each second. That allows them to take 32 x 32 pixel images at the rate of 14 frames per second.

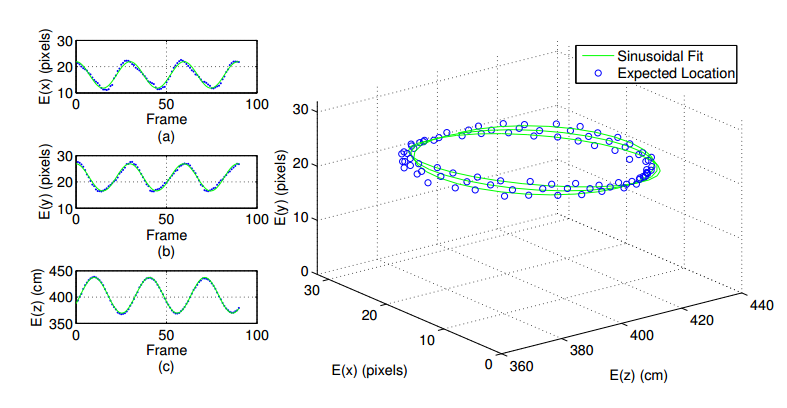

To test the device, they videoed a three-dimensional pendulum consisting of a baseball suspended from the ceiling by a 170 centimetre rope and swinging in a circle with a solid angle of approximately 25 degrees.

By looking at the changes between each image, they were able to track the position of the baseball accurately as it swung.

That’s impressive because the system is simple and easy to scale to high resolution, at least compared to conventional 3D imaging systems. “Our system is much easier to scale to high spatial-resolution than existing photon-counting lidar systems without increased cost or complexity,” they say.

This kind of imaging is particularly useful for lowlight conditions where object tracking is otherwise tough. So an interesting question is where it might best find application. Answers please in the comment section below.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1309.4385: Photon Counting Compressive Depth Mapping

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.