How Google Converted Language Translation Into a Problem of Vector Space Mathematics

Computer science is changing the nature of the translation of words and sentences from one language to another. Anybody who has tried BabelFish or Google Translate will know that they provide useful translation services but ones that are far from perfect.

The basic idea is to compare a corpus of words in one language with the same corpus of words translated into another. Words and phrases that share similar statistical properties are considered equivalent.

The problem, of course, is that the initial translations rely on dictionaries that have to be compiled by human experts and this takes significant time and effort.

Now Tomas Mikolov and a couple of pals at Google in Mountain View have developed a technique that automatically generates dictionaries and phrase tables that convert one language into another.

The new technique does not rely on versions of the same document in different languages. Instead, it uses data mining techniques to model the structure of a single language and then compares this to the structure of another language.

“This method makes little assumption about the languages, so it can be used to extend and refine dictionaries and translation tables for any language pairs,” they say.

The new approach is relatively straightforward. It relies on the notion that every language must describe a similar set of ideas, so the words that do this must also be similar. For example, most languages will have words for common animals such as cat, dog, cow and so on. And these words are probably used in the same way in sentences such as “a cat is an animal that is smaller than a dog.”

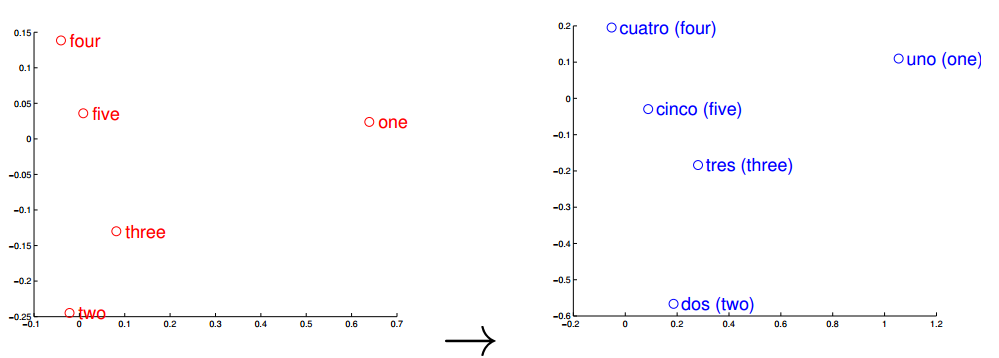

The same is true of numbers. The image above shows the vector representations of the numbers one to five in English and Spanish and demonstrates how similar they are.

This is an important clue. The new trick is to represent an entire language using the relationship between its words. The set of all the relationships, the so-called “language space”, can be thought of as a set of vectors that each point from one word to another. And in recent years, linguists have discovered that it is possible to handle these vectors mathematically. For example, the operation ‘king’ – ‘man’ + ‘woman’ results in a vector that is similar to ‘queen’.

It turns out that different languages share many similarities in this vector space. That means the process of converting one language into another is equivalent to finding the transformation that converts one vector space into the other.

This turns the problem of translation from one of linguistics into one of mathematics. So the problem for the Google team is to find a way of accurately mapping one vector space onto the other. For this they use a small bilingual dictionary compiled by human experts–comparing same corpus of words in two different languages gives them a ready-made linear transformation that does the trick.

Having identified this mapping, it is then a simple matter to apply it to the bigger language spaces. Mikolov and co say it works remarkably well. “Despite its simplicity, our method is surprisingly effective: we can achieve almost 90% precision@5 for translation of words between English and Spanish,” they say.

The method can be used to extend and refine existing dictionaries, and even to spot mistakes in them. Indeed, the Google team do exactly that with an English-Czech dictionary, finding numerous mistakes.

Finally, the team point out that since the technique makes few assumptions about the languages themselves, it can be used on argots that are entirely unrelated. So while Spanish and English have a common Indo-European history, Mikolov and co show that the new technique also works just as well for pairs of languages that are less closely related, such as English and Vietnamese.

That’s a useful step forward for the future of multilingual communication. But the team says this is just the beginning. “Clearly, there is still much to be explored,” they conclude.

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1309.4168: Exploiting Similarities among Languages for Machine Translation

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.