New Approach to Making Graphene Could Lead to Workable Transistors

Researchers at Stanford have used DNA as a template to synthesize ultra-thin ribbons of graphene directly on silicon wafers. This new approach could ultimately lead to graphene transistors that leak less current and are thus more practical for electronics.

Graphene, a single-atom-thick carbon material first discovered in 2004, has electronic properties that make it attractive for use in integrated circuits. Electrons move much more quickly through graphene than silicon. But even the best graphene transistors are impractical for use in circuits because the material lacks a bandgap—a property of semiconductors that allows transistors to be switched on and off by changing the amount of current running through them. With graphene transistors, there’s too little difference between the amount of current running when they’re switched on versus when they’re off. This causes them to leak excessive amounts of current while in the off state.

Recent theoretical work and experimental evidence has suggested, however, that graphene ribbons less than 10 nanometers wide will exhibit a bandgap. But it’s very difficult to synthesize graphene structures of such dimensions and place them in the exact locations needed to be part of an electronic circuit. A group led by Zhenan Bao, a chemical engineering professor at Stanford, has now grown such graphene nanoribbons directly on silicon wafers.

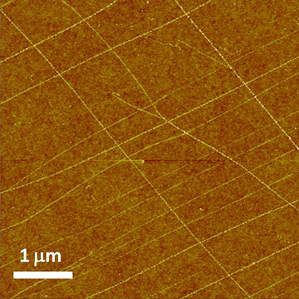

To guide the placement and alignment of the ribbons, Bao used DNA. She and her colleagues spin-coated silicon substrates with a solution containing bundles of double-stranded DNA, the dimensions of which can be tuned by varying the composition of the buffer in the solution. The process results in thin DNA bundles as long as 20 micrometers aligned on the substrate. The researchers then infused the DNA with copper ions, and heated it at very high temperatures in the presence of methane gas and hydrogen. Graphene ribbons less than 10 nanometers wide formed from carbon that had comprised the DNA and methane, via a reaction catalyzed by the copper ions. (Bao notes that the ribbons aren’t perfect, and some regions have more than a single layer of carbon atoms, so they are more precisely called “graphitic.”) The research is described in a paper recently published in Nature Communications.

The group showed that the ribbons could be used in working transistors. Much about the method will need to improve if it is going to produce high-performing circuits. But the demonstration, says Bao, “opens up a new path” that could lead to a method for manufacturing graphene transistors and circuits at a large scale.

The approach is “very clever,” says James Tour, a chemistry professor at Rice University. Tour cautions that so-called bottom-up fabrication approaches like this one still have a long way to go to produce graphene structures precisely where they are needed. “For integration into large-scale systems, the traditional top-down approach is still hard to beat for alignment and placement,” he says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.