“Tamper-Proof” Chips, with Some Work, Might Give Up Their Secrets

For high-security jobs like protecting military plans or corporate secrets, the last line of defense is to keep cryptographic keys and other crucial data on chips covered by elaborate physical protections, such as layers of wire mesh that will destroy the stored data if disturbed.

Even this probably isn’t enough, as it turns out. Researchers in Berlin and California have shown that with costly equipment and determination, it’s possible to mill down the back of the silicon on chips and steal the data with microscopic probes. It’s akin to bank robbers digging up from underground to reach a highly protected vault.

The research “is nice work that establishes that there is a new class of attacks that should be considered if invasive attacks are a concern,” says Srini Devadas, a computer scientist at MIT. Such invasive attacks might be used, he says, on a smartphone bearing secrets that was “left in a hostile territory.”

The attack—pulled off by researchers at the Technical University of Berlin together with Christopher Tarnovsky, vice president of semiconductor services at IO Active, a security company in Seattle—was used to prove a general concept. It involved a chip made by Atmel that is found in products like the TiVo video recorder. It’s far from being the latest or most secure kind of chip available, but the researchers argue that by using more advanced equipment than they had available, their method could work against newer and more sophisticated chips.

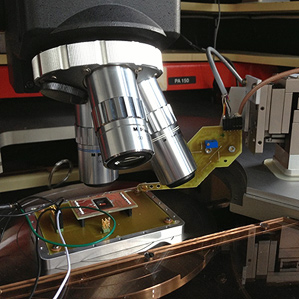

The researchers started by using a polishing machine to gradually mill the back of the silicon until it was only 30 micrometers thick. Then they put the thinned chip under a scanning laser microscope fitted with an infrared camera and watched where key operations were happening. “We can see the heat emissions and know this is where it is running when the encryption algorithm starts to crunch numbers,” Tarnovsky says.

From there they used an expensive piece of equipment called a focused ion-beam machine to dig tiny trenches—to as thin as two micrometers—to edit features on the chip. This made it possible to use tiny probes that could essentially wiretap communications channels on the chip and extract data.

The work will be presented at a computer security conference in Berlin in November.

Given the expensive equipment required, “the overall cost of the attack will be prohibitively high to most attackers, leaving only a few well-advanced labs to carry out such work,” says Sergei Skorobogatov, a computer scientist at Cambridge University.

Nonetheless, the research is valuable for showing that physical protections on chips have their limits, says Radu Sion, a cloud security researcher and computer scientist at Stony Brook University. “The assumption in the software community, including the cryptographic community, is that when you put something on a chip: ‘Hey man, these things are hard to touch, hard to get to.’ This shows this is not exactly true,” he says. “Things are not as clear-cut as people thought before. There is no tamper-proof chip.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.