The Quest for an Artificial Liver

the body.

Prometheus, the mythological figure who stole fire from the gods, was punished by being bound to a rock. Each day, an eagle swept down and fed on his liver, which then grew back to be eaten again the next day.

Modern scientists know that the liver can indeed regenerate itself if part of it is removed, says MIT engineer Sangeeta Bhatia, a professor of health sciences and technology and of electrical engineering and computer science. However, researchers trying to exploit that ability in hopes of producing artificial liver tissue for transplantation have repeatedly been stymied: mature liver cells, known as hepatocytes, quickly lose their normal function when removed from the body.

Now Bhatia and colleagues have taken a step toward artificial liver tissue. They have identified a dozen chemical compounds that can help liver cells not only maintain their normal function while being grown in a lab dish but also multiply to produce new tissue.

Cells grown this way could help researchers develop engineered tissue to treat many of the 500 million people suffering from chronic liver diseases such as hepatitis C.

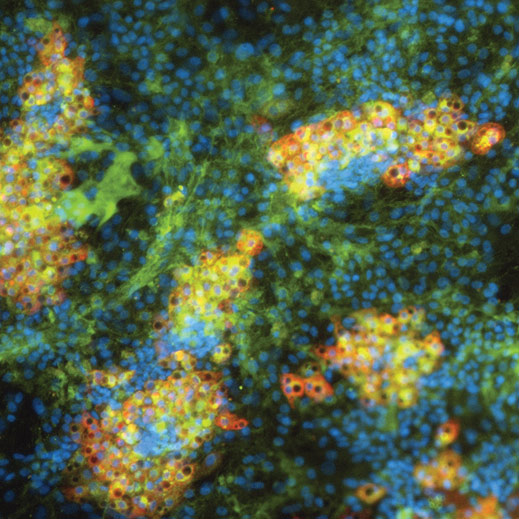

Bhatia, who is also a researcher at the Broad and Koch institutes as well as the Institute for Medical Engineering and Science, previously developed a way to temporarily maintain normal function in liver cells removed from the body; the key was precisely intermingling them with mouse fibroblast cells. For this study, the research team adapted the system so that the liver cells could grow, in layers with the fibroblast cells, in small depressions in a lab dish. This allowed the researchers to perform large-scale, rapid studies of how 12,500 different chemicals affect liver-cell growth and functions, including drug detoxification, energy metabolism, protein synthesis, and bile production.

That screen identified 12 compounds that helped the cells divide, maintain their normal functions, or both.

Bhatia and colleagues have also recently made progress on another challenge in engineering liver tissue: getting the recipient’s body to grow blood vessels to supply the new tissue with oxygen and nutrients. Working with Christopher Chen, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Bhatia showed that if preformed cords of endothelial cells are embedded into the tissue, they will rapidly grow into arrays of blood vessels after the tissue is implanted.

“Together, these papers offer a path forward to solve two of the long-standing challenges in liver tissue engineering—growing a large supply of liver cells outside the body and getting the tissues to graft to the transplant recipient,” Bhatia says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.