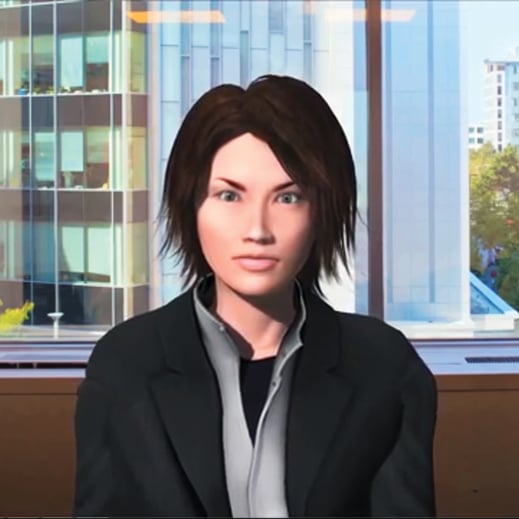

New software developed at MIT can help people who have difficulty with interpersonal skills practice until they feel more comfortable with situations such as a job interview or a first date. The software, called MACH (for “my automated conversation coach”), uses a computer-generated onscreen face, along with facial, speech, and behavior analysis and speech synthesis software, to simulate face-to-face conversations. It then gives users feedback on their interactions.

The research was led by MIT Media Lab doctoral student M. Ehsan Hoque, PhD ’13, who says the work could be helpful to a wide range of people, including those with Asperger’s syndrome. “Interpersonal skills are the key to being successful at work and at home,” Hoque says. With his system, he says, people have full control over the pace of the interaction and can practice as many times as they wish. And in randomized tests with 90 MIT juniors, the software showed its value.

It runs on an ordinary laptop, using its webcam and microphone to analyze the user’s smiles, head gestures, and speech volume and speed, among other things. The automated interviewer can smile and nod in response to the subject’s speech and motions, ask questions, and give responses.

Each participant had two simulated job interviews, a week apart, with different MIT career counselors. Between those interviews, the students were split into three groups. One watched videos of general interview advice; the second had a practice session with MACH and watched a video of their performance but got no feedback; a third group used MACH and then saw videos of themselves along with graphs showing when they smiled, how well they maintained eye contact, how well they modulated their voices, and how often they used filler words such as “like,” “basically,” and “umm.”

Evaluations showed statistically significant improvement by members of the third group on measures such as whether the counselor would “recommend hiring this person.” There was no significant change for the other two groups.

One reason the automated system gives effective feedback, Hoque believes, is precisely that it’s not human: “It’s easier to tell the brutal truth through the system because it’s objective.”

At press time Hoque expected to earned a doctorate in media arts and sciences at MIT over the summer and become an assistant professor of computer science at the University of Rochester this fall.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.