A Clean Race

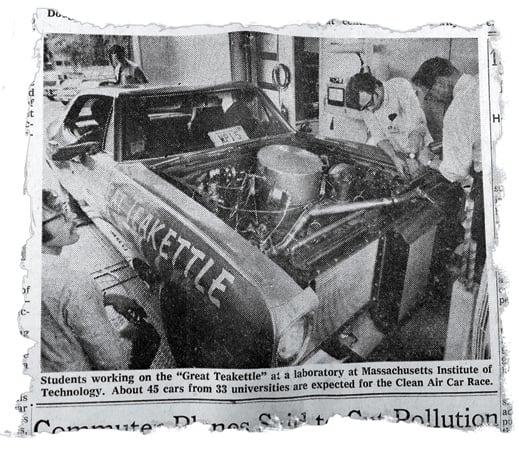

Before the sun rose over Massachusetts Avenue on an August Monday in 1970, a colorful array of 43 cars modified by students rolled up to the starting line. Camera crews lined the dark street to catch the beginning of the Clean Air Car Race, a six-day drive over 3,600 miles of highway from MIT to Caltech to see who could make the best time in a low-emission car. Student engineers from colleges nationwide were out to prove that it was possible to slash automobile air pollution with existing technology.

“The timing of the race couldn’t have been better,” says race organizing committee chair Bob McGregor ’69, SM ’70. Smog had become a national concern, and California arguably had it the worst. In warm months, it sent Pasadena’s schoolchildren home and draped a yellow-brown curtain over the San Gabriel Mountains. As California led the way in reforming emission standards, the U.S. government launched a plan to nationalize those rules.

MIT and Caltech had competed against each other in a cross-country electric-car race in 1968, but this time the professors in charge decided to open the competition to all universities and all types of low-pollution vehicles. Organizers spent intense afternoons designing the scoring formula by which one overall winner could be chosen from the best performers in five categories: modified traditional internal-combustion engines, hybrid electrics, pure electrics, steam engines, and gas turbines. A car’s pre-race emission tests, durability, and noisiness would count. To qualify, cars had to meet tightened emission standards that were set to take effect in 1975; they earned heavy penalties for emitting the dirty tailpipe trifecta of unburned hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, and oxides of nitrogen. Power-plant emissions were taken into account when calculating the scores for electric cars.

The race was a big deal, and not just to students. Companies such as General Motors and Ford donated cars and money for a chance to appear future-minded. The National Air Pollution Control Administration leaped at the chance to promote sustainability. For MIT, which had recently made the controversial decision to divest itself of its instrumentation lab in response to campus Vietnam protests, it was an opportunity for some positive press. “Gentlemen,” MIT Corporation president James Killian told the organizers, “I need a good success story, and you are going to be it.” Life magazine published a spread of young men and women standing beside their cars in MIT’s Great Court on the morning of the race.

To make sure the electric cars would be able to recharge, Ron Francis ’72, SM ’73, and Bill Charles ’68 took to the road, making their pitch to selected utilities along the route. “Think of your market share for electric power if this turns into an advantageous technology!” Charles told the executives. Their persistence paid off. Every 50 miles, a company installed a charging station to which it supplied power. It was the first U.S. transcontinental electric highway, something Tesla Motors is only now building for its luxury Model S. Still, the electric cars all fell far behind. “When everybody else was running at 60 miles an hour or more, some electrics had to stop every hour to get recharged and then charge for an hour,” says organizing committee member Craig Lentz, SM ’71. The race organizers, who hadn’t foreseen that charging would take so long, realized too late that they should have given the electric cars a two-day head start.

MIT’s two entries ranked among the most memorable. The Institute’s hybrid electric had to be towed across the finish line. Its gas turbine car ran on jet fuel, requiring the MIT team to tote the 1,000-pound turbine on a truck to the nearest airport at dawn when they needed to refuel. “They had police pulling them over along the way,” says McGregor. The only car of its kind, it automatically took first place in the category, though its vertically blasting exhaust tore the finish line banner into Swiss cheese.

An independent panel of experts declared Wayne State University’s modified internal-combustion car the overall winner. This success with mainstream technology foreshadowed the industry’s main approach to reducing emissions in the years to come. Since 1970, steady progress on exhaust catalysts has cut emissions per vehicle by a factor of more than 100, says mechanical engineering professor John Heywood, SM ’62, PhD ’65, the race’s faculty advisor and MIT’s Sloan Auto Laboratory director from 1972 to 2009. Yet we still have a long way to go to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions from cars in the coming decades. “So the story has changed, but it also hasn’t changed,” he says. “The best bet is often to improve something that’s already working.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.