How Footprint Recognition Software May Help Zoology

Studying animal behavior in the wild usually starts with figuring out just where the wild animals are hiding. Field biologists can use a combination of methods—radio collars, aerial surveys, and camera traps—to remotely monitor animal movement. However, to an expert eye, a well-preserved footprint can also reveal a surprising amount about an animal—its species, gender, age, even its individual identity.

The trick is being able to do that accurately and quickly. Over the last decade, WildTrack, an organization founded by zoologist and veterinarian Zoe Jewell and her husband, Sky Alibhai, has been developing image processing software to detect physical footprint characteristics that are hard for an untrained eye to recognize. The organization’s software is being used to track a variety of animals in different habitats, including Amur tigers in Russia, tapir in South America, and polar bears in the Canadian province of Nunavut.

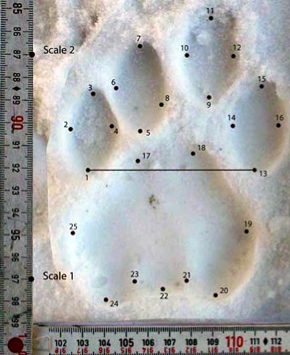

Jewell and Alibhai call their method footprint identification technique, or FIT. Professional trackers photograph footprints (with a ruler for scale) and add GPS coӧrdinates. The footprints are then loaded into software that allows WildTrack to match them to a large number of known footprints from captive animals of the same species. Algorithms compare elements of the photographed footprint against those in a database of animals whose age and gender are known.

Jewell and Alibhai got the idea for WildTrack while working with black rhino in Zimbabwe in the late 1990s. It’s taken years of tweaking and tinkering to develop algorithms that reliably recognize footprints of a given species.

An ongoing challenge will be FIT’s reliability (it is currently 90 percent accurate at correctly determining the sex, age, and species). Nonetheless the technique is low cost, relatively easy to use, and noninvasive compared to radio collaring, which requires darting an animal. But FIT doesn’t work well with all animals yet and is still very much in an experimental stage. “The zebra hoof is a big challenge because it’s hard to mark different shapes. On the other hand, a cheetah or lion footprint, where you have four toes and a heel pad, there’s lots of complexity there,” making it easier to identify individuals, Jewell says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.