Stem Cell Eye Cells Tested in Mice

Scientists in the U.K. have produced rod-like photoreceptors from embryonic stem cells, and successfully transplanted them into the retinas of mice. The work suggests that embryonic stem cells could perhaps one day be used as a treatment for patients who have lost their vision to retinitis pigmentosa, macular degeneration, or other degenerative conditions in which the light-detecting rods and cones of the retina die over time.

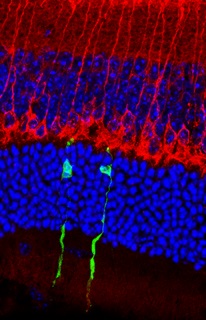

embryonic stem cells (green) integrate into

the damaged retina of an adult mouse and

touch the next neuron in the retinal circuit (red).

Currently, there are few treatment options for these conditions; electronic implanted devices are available for some patients in some countries, but their efficacy is limited (see “A Second Artificial Retina Option for the E.U.” and “What It’s Like to See Again with an Artificial Retina”). The new work, reported in Nature Biotechnology on Sunday, offers hope for a more effective, comprehensive treatment.

The researchers used a new method for growing embryonic stem cells that enables them to turn into immature eye cells and self-organize into three-dimensional structures similar to those seen in a developing retina (see “Growing Eyeballs”). Immature light-detecting cells were harvested from this culture and transplanted into the retinas of night-blind mice. There, the cells integrated with the natural cells of the eye and formed synaptic connections. The work did not involve testing how well the mice could see after the cells were implanted.

While this particular technique is probably years away from human trials, embryonic stem cells are already being tested in clinical trials for macular degeneration and Stargardt’s macular dystrophy. Last week, in fact, Japanese authorities announced that an alternative source of stem cells will soon move into human trials as a treatment for eye disease. The BBC reported that Japan has approved the first clinical trial of induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPS cells. These stem cells are made by reprogramming normal adult cells so that they return to a more embryonic-like state so that they can then be converted into other cell types, such as retinal cells. In the clinical trial, doctors will collect a patient’s own cells, which will then be used in an experimental treatment for age-related macular degeneration. The trial will start with around six patients.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.