Scientists Size Up U.S. Carbon Storage Potential

How much carbon dioxide could the U.S. store underground? The answer depends on both geology and engineering, and estimates of the nation’s storage capacity have varied widely. Now the United States Geological Survey has weighed in, releasing its first-ever “detailed national geologic carbon sequestration assessment.” The study, which refers to today’s engineering practices as well as “current geologic and hydrologic knowledge of the subsurface,” concludes that there are enough “technically accessible” onshore storage resources to accommodate 500 times the country’s total energy-related emissions in 2011.

This may seem like great news, but it should be taken with more than a pinch of salt. In reality, the extent to which we can rely on carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology is very unclear. The technology—which generally entails capturing carbon dioxide at a power plant, compressing it to a near-liquid state, and injecting it into porous rock formations deep underground—is prohibitively expensive, and has yet to be tested at the scale required to significantly dent emissions. Some researchers have also raised questions about the viability of large-scale CCS because it could induce earthquakes (See: “Researchers Say Earthquakes Would Let Stored CO2 Escape”). And, perhaps most importantly, each candidate site is unique; recent research has shown that individual storage sites can exhibit very different geomechanical responses to carbon dioxide injection.

All this is why it’s worth keeping eye on Canada’s plan to use CCS to reduce the carbon footprint of its growing oil sands industry—an important first test of CCS as a legitimate tool for cutting emissions. (See “Can Carbon Capture Clean Up Canada’s Oil Sands?”)

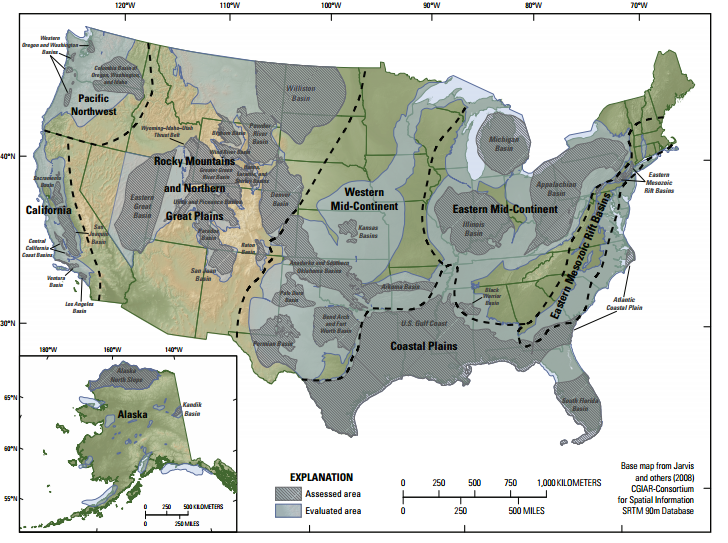

Meanwhile, below is a map showing the various sedimentary basins the USGS assessed for the study. The dark grey areas indicate sites that were assessed, and lighter grey represents evaluated areas that were not assessed because they failed to meet certain minimum requirements for carbon dioxide storage.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.