We’ve all experienced the sense of being familiar with somebody without knowing their name or even having spoken to them. These so-called “familiar strangers” are the people we see every day on the bus on the way to work, in the sandwich shop at lunchtime, or in the local restaurant or supermarket in the evening.

These people are the bedrock of society and a rich source of social potential as neighbours, friends, or even lovers.

But while many researchers have studied the network of intentional links between individuals—using mobile-phone records, for example—little work has been on these unintentional links, which form a kind of hidden social network.

Today, that changes thanks to the work of Lijun Sun at the Future Cities Laboratory in Singapore and a few pals who have analysed the passive interactions between 3 million residents on Singapore’s bus network (about 55 per cent of the city’s population). ”This is the first time that such a large network of encounters has been identied and analyzed,” they say.

The results are a fascinating insight into this hidden network of familiar strangers and the effects it has on people.

All this is made possible by the Singaporean bus service’s smart card ticketing system. Lijun and co studied an anonymised data set of more than 20 million bus journeys taken during a single week by 2.9 million different people. They particularly studied “in-vehicle encounters” in which two individuals are present on the same bus at the same time.

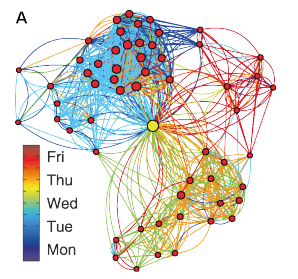

The pattern of in-vehcicle encounters is rich, and the results of their analysis make for interesting reading. Lijun and co found some 18 million encounters of this kind during a single week. These encounters showed a strong repeating pattern with peaks at periods of 24 hours, 48 hours and 72 hours.

Further study revealed that about 85 per cent of these repeated encounters happen at the same time of day and that individuals were more likely to encounter familiar strangers in the morning than the afternoon. “We confirmed that repeated encounters tend to happen more often in the morning, suggesting that collective regularity is more pronounced in the morning than in the afternoon,” say the team.

One interesting question is what drives these encounters and Lijun and co show that it is largely the result of similar behaviour patterns rather than random meetings. In other words, humans are creatures of habit and that these habits can become synchronised both in time and in space. Indeed, the more regular an individual’s behaviour, the more likely he or she is to have regular encounters.

Perhaps the most interesting result involves the way this hidden network knits society together. Lijun and co say that the data hints that the connections between familiar strangers grows stronger over time. So seeing each other more often increases the chances that familiar strangers will become socially connected.

That’s a fascinating insight into the hidden social network in which we are all embedded. It’s important because it has implications for our understanding of the way things like epidemics can spread through cities.

Perhaps a more interesting is the insight it gives into how links form within communities and how these can strengthened. With the widespread adoption of smart cards on transport systems throughout the world, this kind of study can easily be repeated in many cities, which may help to tease apart some of the factors that make them so different.

For the ordinary commuter, it is a refreshing reminder that we are all part of an important network that we know little about. Next time you see a familiar stranger, you can be sure you have much in common in terms of your spatial and temporal behaviour patterns. Why not introduce yourself and see what happens?

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1301.5979: Understanding Metropolitan Patterns of Daily Encounters

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.